Boomerang House in the inner-city Brisbane suburb of Ascot is the residence of partners in life and work, Joe and Hayley Adsett, and their two young children, Julian and Madeline. As an architect and the founder of eponymous studio Joe Adsett Architects, Joe designed the home to his and Hayley’s own brief, placing functional family living at the core of each thoughtful detail. Constructed by high-end residential builder-developers Graya, the home is configured in an L-shape, taking full advantage of the large 1200-square-metre block. The practical configuration of the home promotes liveability, with the separate living spaces each connecting to the glittering pool and garden, altogether enhancing the connection between indoors and out.

Boomerang consists of five bedrooms, including a parents’ retreat, five bathrooms, a four-car garage, underground wine cellar, upper-level lounge and a light filled downstairs living area. The enormous square-shaped block also facilitates a 9-metre swimming pool and tennis court for the whole family to enjoy. With oversized windows featuring throughout the home, the remarkably light-filled property feels grand and impactful on all levels. At the same time, the architectural response by Joe Adsett Architects reacts to the high-energy dynamic of family life and living.

Boomerang House in Brisbane by Joe Adsett Architects

Grand in scale and impressive in nature, Boomerang signals one of the largest residential projects ever undertaken by Brisbane-based Graya. “This was one of the biggest homes Graya has built and we’d never completed a home with a tennis court,” says Rob Gray from Graya. But despite its size, the property still manages to feel relaxed enough to accommodate family living. “It was a great challenge and we enjoyed watching it all come together,” Rob adds.

Curved geometry defines the inside space, imbuing an organic sense of calm across the home. Statement architectural features are layered throughout the interior in a palette of fresh white and soft grey, juxtaposed with striking furnishings, while floor-to-ceiling windows and sliding doors enable natural light to flood the lower-level living area, maximising the connectivity with the outdoor space. “This was [architect] Joe’s personal home, so he wanted it to be functional for his family, bringing the inside out and connecting key interior and external design elements,” Rob explains.

The defining feature of the downstairs living area is a swirling helical stairway that joins two floors of the residence. “This was the first curved stairway we created,” Rob admits, in the same breath singing the praises of the plasterboard used to create the sinuous effect. The magnificent sculptural masterstroke was formed with CSR Gyprock’s premium Flexible plasterboard. Designed to impress, the product enables specifiers, designers and installers to easily create “architecturally defining moments” such as curved walls, ceilings and stairways.

The stairway culminates in a beautiful wrap-around library, complemented by a circular skylight which enables light to fill a spectacular void that traverses the three-storey home. Impressive, impactful and breathtaking, the skylight and void were also created using Gyprock Flexible, demonstrating how elevated design thinking, coupled with great craftsmanship, can shape basic building materials into modern-day masterpieces.

The stairway culminates in a beautiful wrap-around library, complemented by a circular skylight which enables light to fill a spectacular void that traverses the three-storey home.

Catch up on more of the latest architectural gestures as well as art projects and exhibitions. Plus, join the mailing list to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.

Related stories

- Could this be the new look for Sydney’s brutalist Sirius building?

- Skinny mini: The pencil thin hotel proposed for Sydney’s skyline.

- Sydney’s biggest pool since the 2000 Olympics is now open.

- Port Douglas retreat: Gurner reveals plans to open luxury hotel in Far North Queensland.

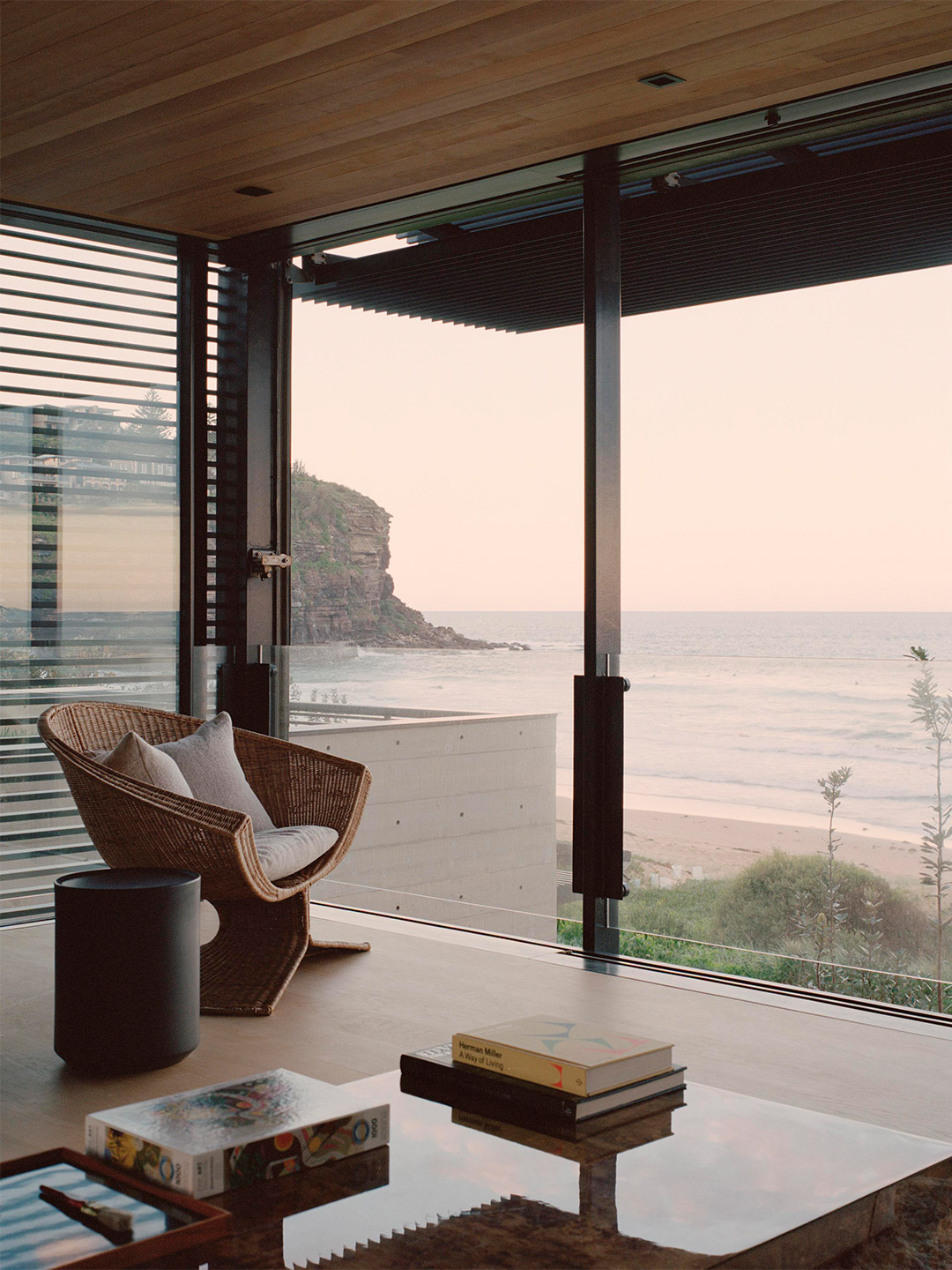

Nestled among the sand dunes of Bilgola Beach, this 873-square-metre family home is located toward the tip of the Northern Beaches peninsula in Sydney. Passing through a grove of palm trees and iconic Norfolk Pines, the site’s entrance leads through the solid volumes of the home’s main and guest wings. Upon approaching the front door, the view opens up to Bilgola’s golden sands and the Pacific Ocean that laps Australia’s east coast.

Responding to the glittering beachfront environment and exposed location between the north and south headlands, the home was designed by Seattle-based architecture firm Olson Kundig to withstand Australia’s dramatic climate conditions, “where harsh sunlight, high winds and flooding are common,” say the architects. It does this not by working against the rhythm of nature, but rather by existing in partnership with it.

Bilgola Beach House in Sydney by Olson Kundig

“The structure is set on concrete piles, allowing sand and water to move in and out beneath the building,” the architects explain. At the same time, the design of the home allows the family who reside here to connect with the natural environment, exampled by the shaded retractable window walls that merge the indoors with out, and provide passive ventilation.

An internal courtyard invites filtered daylight into the core of the home, where a central water feature helps to cool the air. The colour of the home’s board-formed concrete walls references the colour of the local sands, “relating the architecture to its site,” the architects suggest, “helping it merge with the natural condition of the headland as it weathers over time”.

The structure is set on concrete piles, allowing sand and water to move in and out beneath the building.

Love the Bilgola Beach House by Olson Kundig? Catch up on more architecture and design highlights. Plus, subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.

Related stories

- Introducing the New Wave collection of 80s-inspired vases by Greg Natale.

- Carla Sozzani curates new colours for classic Arne Jacobsen chairs.

- Adam Goodrum stamps all-Australian style on new breezeblock design.

Architects EAT was founded in 2000 by design duo Eid Goh and Albert Mo. One of their most recent projects is Bellows House, a rather unexpected beach retreat in Flinders – a seaside town in Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula. Almost brutalist in its architectural style, Bellows House employs concrete blocks and brick paving both as structural and aesthetic elements. The intricacies of the forms created with these materials rebound light in spectacular ways, illuminating the house with a unique lambency.

The exterior showcases frustum roofs, an angular, sloping structure that distinguishes the house from those around it. Viewed from the street, this feature offers a novel dimension to the home, evoking the curiosity of those on the outside looking in. But once inside the home, the two largest of the frustum roofs reveal their unique and geometric structure – a sort of reverse-stepped concrete pyramid.

Bellows House in Flinders by Architects EAT

It is unusual for the ceiling of a property to be the central feature, however, the pyramidal roof structure creates an appealing contrast; its stepped surface catches sunshine from the central skylight which then facilitates a dance of light and shadow in all four corners of the living space. Poised within this geometric roof arrangement, there is a chrome-cross structure, from which mid-century style pendant lights hang in a metal orbit.

Another key design feature of the home is the concrete breezeblocks on the exterior wall. These blocks are featured both on the half-height wall at the gate of the property and on the walls surrounding the perimeter of the home. The way in which they are placed offers a sense of weightlessness; a type of ‘cut through’ in contrast to the solid, light grey blocks that clad the majority of the home. These blocks continue to the interior of the home protruding from the classic block wall; a small row of them at hip-height by the front door offer ideal shelf space for keys.

Returning outside, the home could be thought of as a modern, coastal compound. A large sliding door, encased in white metal separates the living-dining space from the outside. In the middle of the courtyard is a garden feature, brimming with native foliage. The heart of the outdoor area centres around a fire-pit, with a timber bench running alongside it. Given the L-shaped format of the home, the outdoor space acts as an open-air meeting point for its two wings.

Block is also used as a design feature in the bathroom. The industrial-style space is equipped with a standing brick vanity and marble sink; the taps are integrated into the large mirror, which again uses light to create depth and dimension within the space. Small, square tiles with a rounded finish soften the harder materials of the room.

These industrial materials flow into the kitchen which is largely comprised of black metal, block and concrete. Despite the simple design, layers are used within each material in a thoughtful way. The base of the kitchen island features earthy-coloured brick, which is the meeting point between the polished concrete and the white brick on top.

The low-slung appearance and frustum roofs of Bellows House certainly give it an edge – and the nickname “The Pyramids of Flinders” – but the muted material palette allows the project to assimilate more cohesively into its coastal surrounds. The quiet blend of aged timber, clay brick and concrete block complements the subtle tones of the local Australian bush, setting a backdrop for many summers by the sea.

From the beginning of the design journey I wanted to design something that is permanent. You know this building, or this house, is designed for 100 years.

This article originally appeared on the Brickworks Design Channel. Catch up on more architecture highlights. Plus, subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.

Related stories

- Incoming oasis: Red Sea International Airport by Foster + Partners.

- Steven Chilton Architects previews 2000-seat theatre inspired by Chinese silk.

- Ateliers Jean Nouvel wins competition to build opera house in Shenzhen.

Perched high on a cliffside plot in Bowen Hills, a suburb just north of Brisbane’s CBD, La Scala is the private residence of Ingrid Richards and Adrian Spence of Richards and Spence. Drawing upon four years of collected ideas, the architects desired to create a house where the outside space acted solidly as its centrepiece. The resulting dwelling – a section of which was resolved by Ingrid with a sketch on a napkin while on holidays – evokes snapshots of the Mediterranean and Central and South America. Its bare masonry standing out under Queensland’s famed blue skies.

Bookended by two distinct sections of the house, the outdoor oasis reads as a multi-level amphitheatre-like arrangement of full- and half-height concrete masonry blocks, laid in horizontal gestures. Gently tiered terraces contain tufted grass and rambling foliage, while glistening reflections off the enticing pool dance across the garden walls. Few homes have an outdoor swimming pool at the heart and, of those few, it’s unlikely any match the glimmering beauty of La Scala.

The home represents a defiant inversion of the norm. “Our town planning regulations are very prescriptive in the way that they assume you are going to put a house in the middle of the block and have a yard around it – and we wanted to do the opposite,” says Adrian. Placing emphasis on the outdoors and specifying raw, light concrete blocks for the construction were appropriate choices in a city that basks in seemingly endless sunshine. The bold material choice also marks a continuing theme for the architecture practice who has employed near-whitewashed concrete blocks in other designs, including the Calile Hotel, with both aesthetics and sustainability in mind.

“For our work in Brisbane, we’ve tended to use a light-coloured masonry,” says Adrian. “I think that’s because we feel it’s appropriate for the hot-weather city we’re in.” Longevity has also played a part in the home’s design, with Richards and Spence giving consideration to the life cycle of the building beyond their own residence, and, according to Ingrid, tapping into “the kind of sustainability that’s about not having to keep rebuilding the same thing over and over again”.

“We thought this building in another 10 years could become a gallery or a restaurant or have some other use beyond purely domestic,” says Adrian. “We try to make things that are flexible so they can endure different types of occupation.” While Adrian describes the masonry as looking “almost like a ruin in the way it’s kind of naked … in its detailing”, the house has a glamorous, sun-kissed vibe that’s undoubtedly ideal for entertaining.

For now, Richards and Spence can do just that, making particular use of the monumental outdoor space – whether for parties or in private. “There’s a point where, if you’re lying in the pool facing the building, you get a silhouette of the sky and it feels really wonderful,” says Ingrid. “It feels like you’re alone even though we’re quite close to the centre of the city.”

We thought this building in another 10 years could become a gallery or a restaurant or have some other use beyond purely domestic.

Related stories

- Home tour: Couldrey House in sub-tropical Queensland by architect Peter Besley.

- Home tour: A contemporary house in Subiaco with quaint cottage appeal.

- Home tour: A concrete house in Singapore with lush tropical gardens.

Locals who wander the foothills of Mount Coot-tha in Queensland, Australia remark that the distinctive, textured brickwork at Couldrey House is akin to sedimentary rock, tree bark or corduroy fabric. Wildly more playful and sweet-toothed with their words, “children say it is cake with icing,” says architect Peter Besley, who designed the recently built home for a member of his own family.

It’s the slender, off-white bricks and the way in which they were laid with lashings of matching mortar that garners so much attention from passers-by. But take a step back from the imaginative chit-chat of the neighbours, and it’s the brave use of brick in the first instance that sets the home apart from most residential architecture in sub-tropical Queensland. “Many houses [in Queensland] tend to hover over the ground with lightweight materials which need re-coating and replacement,” says Peter. “I instead designed Couldrey House to spring directly from the subterranean rock and to be made of heavy materials lasting a very long time.”

The decision to use masonry at Couldrey House was one that was made early in the design process and, together with the concrete superstructure, it firmly anchors the house to its rocky foundations. “The building is designed to be immensely heavy,” says Peter, who recognises that this home, west of Brisbane, parallels his architectural work in the Levant, particularly in Iraq. “Buildings there seem aware of the scale and solemnity of the land in which they sit,” he says. “The forms and spaces are compelling but simple. They sit heavily on the ground. They seem to say to the landscape: ‘I can accompany you in your long journey’.”

There is a shared monumentality between building and landscape, even when that monumentality is intimate.

Couldrey House is wrapped in a brick envelope, shaped in a simple rectangular prism, says Peter, which is open to the views and breezes of the north and east. The home is completely closed off to the south and harsh conditions of the western side. On the street-facing western elevation, the brickwork is folded in concertinas, in a reducing scale-play around the main entrance door. This design detail and its shadows, benefited by the frothy, whipped cream-like mortar, has its greatest impact in the afternoon light. A similar expression of brickwork stretches horizontally along the western facade and forms a set of stairs, laid in a way so that the brick’s extrusion holes are exposed for drainage.

To the south, Peter specified large horizontal slots in the facade to create “louvres” which adopt a dual role as shading and privacy devices. The house has parapet walls and no overhangs – its flat, internally draining concrete roof is piled with stones. The roof also has what Peter calls “plug and play” functionality whereby various tech-centric contraptions such as antennas, satellites, solar hot water tanks and photovoltaics can be added or removed as technology evolves with no impact on the house.

In response to Queensland’s evolving climate situation, Peter says, “it is now hot-dry as much as it is hot-wet”. An observation that he believes allowed for a hybrid approach to cooling the home – one that goes beyond the traditional reliance on intermittent breezes only. While the home does continue the region’s tradition of catching cooling breezes with its good aspect and a permeable layout, Peter explains that the house is designed to create radiant cooling using thermal mass via its 30 nine-metre-long precast concrete floor and roof units. “Diurnal temperature difference recharges the thermal mass at night, ready to cool the residents each day,” he says. “Radiant cooling does not rely on air, so [this] supplements traditional convection cooling and humidity control.”

The internal configuration of the two-level home is clean and straightforward, but it flips the standard floor plate arrangement on its head. The common spaces are housed in the upper level of the home and the bedrooms are positioned underneath. When combined with the home’s tall ceilings, this planning technique provides the residents with a feeling of living high in the tree canopy – a sensation that’s accentuated by the approach to glazing. Upstairs, the windows start at one metre above floor height as opposed to running floor-to-ceiling which ensures openness but also provides privacy from the street and creates “a nest-like experience for the occupants”.

While the builders have packed away the tools and the project is officially finished, Peter says Couldrey House, in a sense, remains incomplete. “The building stands waiting for endless cycles of weather to be cast down upon it, to gain the finer patinas of age.” Plants are yet to overrun the masonry envelope, says Peter, not least from the two 25-metre-long elevated planter boxes. “The building should get better, not worse, with time.” The neighbours will no doubt call that the cherry on top.

Related stories

- Home tour: A contemporary house in Subiaco with quaint cottage appeal.

- Home tour: WOWOWA’s castle by the creek.

- Home tour: A concrete house in Singapore with lush tropical gardens.

Locals who wander the foothills of Mount Coot-tha in Queensland, Australia remark that the distinctive, textured brickwork at Couldrey House is akin to sedimentary rock, tree bark or corduroy fabric. Wildly more playful and sweet-toothed with their words, “children say it is cake with icing,” says architect Peter Besley, who designed the recently built home for a member of his own family.

Subiaco House, however, is far from cliché.

Designed and coordinated from nearly 4500 kilometres away by Brisbane-based architecture practice Vokes and Peters, the two-storey family abode is located on a prominent corner block and wears a distinctive bell-shaped ‘top hat’ clad in petite terracotta shingles.

At ground level, the suburban home engages politely with the conservative streetscape through its classic timber bay windows. It responds more openly through its adjoining ‘public’ courtyard garden: a generous lawned space which is directed toward the footpath and bordered by a multi-use cloister that extends from the main dwelling.

Both private and public interactions are filtered throughout the cloister, which doubles as an open-air pathway and occupiable extra ‘room’ partially screened by large vertical louvres and developing gardens. Through this contemporary cloister technique, and the flurry of activity that it generates, the line between inside and outside is constantly blurred. So, too, is the boundary between the public sphere and private residential spaces.

The push-and-pull of public and private realms is less at play when it comes to the upper level of the home. Observing Subiaco House from the street, the charming terracotta roof tiles are the home’s most attention-grabbing gesture. But cocooned behind this veil, the upper-level program of the house is kept almost completely out of sight – the only reminder of the second storey’s existence is the sparingly placed windows on its elevations.

While the home and its garden-rich setting can be seen to reference the well-groomed visage of its Federation-era neighbours, there are also influences from formal European plazas and immaculate country cottages, both in the planning and the impressive craftsmanship of the home.

It’s unusual for a modern home to be so thoughtfully layered with detail and craftsmanship but at Subiaco House, this is part of its DNA. Glimpses of the intricate network of rafters, battens and struts are offered from the outside. The rainwater heads align in absolute precision with the notched concrete edges of the cloister. The underside of the same concrete plane features patterned impressions, discoverable only when the passer-by takes the opportunity to direct their gaze upward. Even the tip of the chimney that extends from the outdoor fireplace is flourished.

It’s unusual for a modern home to be so thoughtfully layered with detail and craftsmanship but at Subiaco House, this is part of its DNA.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the interiors of Subiaco House are equally considered and rich in detail as the outward-facing elements. Tile, stone, brick, concrete and timber unite in a harmonious interplay that is quintessentially the design language of Vokes and Peters. Here, the brick-pattern paving of the cloister makes its way confidently indoors and is joined by the same impression technique in the concrete overhead.

When the house is opened up to the daylight, sightlines from within the home extend along the walkways out to the nearby streetscape, further drawing together indoor-outdoor spaces and private-public worlds.

By overcoming geographical distance and stringent development guidelines that favoured a single-storey dwelling, Vokes and Peters have realised a home that further adds to the local fabric of a tightly held suburb. The shared vision of the architect, homeowner and skilled tradespeople sees the new home – a contemporary cottage fit for its custodians – comfortably rubbing shoulders with its heritage neighbours.

Related stories

- 2020 Houses Awards: Australia’s best homes revealed.

- Vokes and Peters wins The Robin Dods Award at the Queensland Architecture Awards.

The maxim ‘the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree’ is particularly pertinent when it comes to interior designer Tamsin Johnson. The Sydney-based style pioneer speaks of how she grew up in a household surrounded by “parents who were aesthetes, antique dealers, art aficionados and decorators” and how this vibrantly creative environment undoubtedly shaped her course.

Ten years after going solo, and with a line-up of impressive interior design projects now under her belt in locations from Sydney and Melbourne to Byron Bay and Paris, Tamsin Johnson caught up with DAN for a quick chat to speak about what’s next in her busy schedule, including a hotel in Marrakesh and publishing a book with Rizzoli. Oh, and you’ll see why we now suspect Trisha Yearwood’s How Do I Live is her go-to karaoke song.

DAN: Can you tell us about yourself, your practice and your approach to interior design?

Tamsin Johnson: I grew up and was schooled in Melbourne, Australia with my sister and parents who were aesthetes, antique dealers, art aficionados and decorators. My father has a jocund spirit and razor-sharp quip and my mother [has] an utterly dogged and fearless work ethic. So, on top of this genetic institution, I think inevitably the interior arts formed me and simply became part of life. My parent’s knowledge and passion for it was indomitable and this left me with no doubt to who I was and what I was going to do.

In 2002, I graduated from RMIT University with a Bachelor of Design in Fashion and hastily moved to London in 2003 and worked for Stella McCartney. Here I met my match, Patch [husband Patrick Johnson], someone of equal passion and fervour and with a uniquely ebullient hutzpah. He magnified all that I loved.

In 2004 I attended the Inchbald School of Design for a formal edge to my training and in 2005 I returned home to Australia to work in Sydney under Don McQualter at Meacham-Nockles-McQualter. With four to five years of practice under my belt, I set out alone in 2010 and have been operating solely ever since. I have two children, and my husband has a successful tailoring business.

A critical objective with any client is two-fold: firstly, to ensure the design sympathises with their personality. And secondly to never let a space to succumb to being ‘decorated’. It must be natural and of human orientation. The spaces need to come alive with the addition of normal life, with the ebb and flow of people.

I’m not comfortable with clutter and the abuse of eclecticism, there is something derogatory in it. To me it implies an imprecision and de-valuing of the other artists’ work that lies within the decorated space. I’m happy to remove the unnecessary. However, I enjoy collision, complexity, drama and calamity – just as much as I enjoy rest, placidity and comfort. There needs to be purpose and beauty in all elements. If I can produce a vigour and spirit in a space that tells you how to feel in it, then I’ve won.

DAN: You have a retail shopfront in Sydney’s Paddington. How did this venture come about?

TJ: We opened the space as an interior design office and then a showcase for various custom pieces and antiques and mid-century furniture but also as a chance to highlight our aesthetic and approach to design.

DAN: What is a current or an ongoing source of creative inspiration for you?

TJ: I allow for traditions in decoration but freshen things with a nod to the contemporary. I’ll take the old with the new, the refined and the dishevelled, a respect for materials and a respect for craft.

I love a sense of travel without leaving the home, a sense of adventure and play. There is a European and North American design language I cherish but it’s more a reflection of its validity to design generally that I’ll harness. Alone, spaces built purely on those premises wouldn’t hold true in Australia, they’d lack something and dissolve away in the mix.

Us Australians are irreverent and impious and it’s that cheekiness laid over a maturity and sort of toughness that I use as my engine for ideas. This toughness is Australian, I think.

There is something wretchedly saturated about our light and how it penetrates a space, it has such severity and I want to revel in it. It activates colour differently – compared to the northern hemisphere – so it needs some taming or muting but at the same time I don’t want to lose its energy and what it does for our mood. Our light seems to collaborate with our sense of fun and oozes a freshness that I want to promote in my work.

DAN: Career highlight(s) so far?

TJ: I’m pretty excited to be launching a book with my favourite publisher Rizzoli next year.

DAN: Has the covid-19 pandemic impacted the way you work or approach design?

TJ: Our business hasn’t changed since covid, luckily. I think our clients are even more focused on making their homes beautiful, calm and comfortable more than ever. We have had lots of old clients repurposing various spaces to adjust to this new way of life.

DAN: What are your top three tips for interior design success?

TJ: That’s a tricky one! I have several…

- Take your time with a space. Particularly at the beginning of a process. It even helps to live in a space first, if possible, so you have a good understanding of how it functions.

- I think it’s always good to use a palette that can be added to [and create] a space that keeps open to being added to over time.

- Leave some empty walls. A room should never be truly finished.

- Try to avoid theming a space. It’s better to layer different periods, eras and origins.

- Enjoy it. Don’t be too precious and don’t over think it. It should be natural, and enjoyable. The spaces that work the least are those that feel overdesigned or feel too ‘decorated’.

Trust your own taste. If you follow this everything will work in harmony in the space.

DAN: What project are you most looking forward to in the future?

TJ: A hotel in Marrakesh.

DAN: Sky’s the limit: what’s a dream project for you?

TJ: All our clients are pretty dreamy… Otherwise, Versailles, I think I could make it more liveable.

DAN: What are the most covetable pieces for you at the moment?

TJ: Lilian O’Neil and Daniel Boyd for Australian art. I collect Daum glass, which I’m always looking out for – particularly from the 1930s. And a horse … I want to start riding again.

DAN: Finally, design-related or otherwise, what’s something we probably don’t know about you?

TJ: My favourite film is Con Air. A much-overlooked classic.

Follow interior designer Tamsin Johnson on Instagram.

Related stories

- Five (or so) minutes with interior designer Fiona Lynch.

- Five (or so) minutes with interior designer Brahman Perera.

Finalists of the eighth annual Architizer A+Awards, revered as “the largest awards program focused on promoting and celebrating the year’s best architecture and products”, have been announced in New York.

Since early January when the awards program opened to submissions, many, if not most, aspects of daily goings-on around the globe are markedly different from those that surrounded last year’s announcement. But one key message remains the same: Architizer’s commitment to highlighting the most pressing issues facing architecture and design today.

News highlights

- The Architizer A+Awards is internationally recognised as “the largest awards program focused on promoting and celebrating the year’s best architecture and products”.

- 2020 marks the eighth year of the prestigious awards program; this year’s finalists have recently been announced out of Architizer’s New York headquarters.

- 11 firms from Australian shores have picked up a sought-after spot on the Architecture category finalists list.

- You are invited to vote for your favourite shortlisted project for the Popular Choice Awards.

To determine the finalists of this year’s A+Awards, 400-plus distinguished jurors from fields that expand beyond architecture including fashion, publishing, real-estate development and technology painstakingly pored over submissions, landing upon an international pool of industry professionals who are practising at the forefront of today’s creative challenges.

11 firms from Australian shores have snagged a sought-after spot on the Architecture finalists list including Koichi Takada Architects, ASPECT Studios, TZANNES, Woods Bagot, Bates Smart, Koning Eizenberg Architecture and Atelier DAU.

“It is a recognition of what I stand for and what I have been seeking to achieve in my professional career over the past two decades,” says Emma Rees-Raaijimakers of Atelier DAU, whose Chimney House project in Sydney’s Redfern has been named as one of five international finalists in the +Living Small category.

“The driving principle behind my creative practice is completely aligned with Architizer’s mission: to nurture the appreciation of meaningful design in the world and champion its potential for a positive impact on everyday life.”

All finalists in the A+Awards are presented online where design practitioners and enthusiasts from around the globe are invited to vote for their favourites during the campaign period. Vote now.

Winners of the Popular Choice Awards are to be honoured alongside jury-nominated winners during the ceremony slated for August 4 in New York.

“In this instance, the Public Choice Award is just as important as the jury’s award,” says Emma. “Even to be nominated with four other international peers is a triumph in itself.”

Even to be nominated with four other international peers is a triumph in itself.

You might also enjoy reading:

Vokes and Peters wins Robin Dods Award at the Queensland Architecture Awards.

Indigenous memorial by Edition Office and Daniel Boyd wins top accolade in ACT.

Finalists of the eighth annual Architizer A+Awards, revered as “the largest awards program focused on promoting and celebrating the year’s best architecture and products”, have been announced in New York.

Comprising renowned architects and academics from across the Sunshine State, the jury for this year’s program presented the awards to more than 20 projects across 14 categories including residential, commercial, sustainable architecture and urban design.

“Each of the awarded projects reflects a response to the environment in their own way,” says jury chair and director of COX Architecture, Richard Coulson. “The projects include opportunities that allow many members of the Queensland public to benefit from good architectural design. They include innovation in technology and materials balanced with a pragmatic response to climate – a hallmark of Queensland architecture.”

Among the individuals and practices recognised during the presentation, architecture firm Vokes and Peters received The Robin Dods Award within the Residential Architecture – Houses (New) category for the coastal abode, Casuarina House.

Casuarina House at the Queensland Architecture Awards

Casuarina House, built by SJ Reynolds Constructions, is a new family home of compact proportions, occupying a coastal subdivision with its own private garden setting. The atypical beachside dwelling has been designed by Vokes and Peters to encourage a connection with the outdoors, facilitated by a long verandah that travels the entire length of the home, and sited to celebrate the coastal lifestyle of northern NSW.

From the outset, Vokes and Peters and the homeowners say they shared the same end goal: to create a garden, not just a home. “Unlike many of the neighbouring houses, the Casuarina House has been pushed to the southern edge of the block to free open space for a large garden that spans the full length of the site,” says the architects. “New living spaces located on the ground floor have large door and window systems allowing the interior to open to the outside. Internal floors are raised on timber platforms, a step above the brick circulation zones to manage sandy feet.”

All projects that received a ‘named’ award or a state award at the Queensland chapter event will be eligible for the Australian Institute of Architects National Architecture Awards to be held later this year.

Casuarina House has been pushed to the southern edge of the block to free open space for a large garden that spans the full length of the site.