WATCH: Global architecture highlights including the Chapel and Meditation Room.

Minho, on the coast of northern Portugal, is a region known for its charming vineyards and river valleys, green-painted fields and a heritage older than the country itself. For it was on these lands that Portugal was founded in 1143. History-rich and immensely fertile, this part of the world is also where Australian-born, Bali-based architect Nicholas Burns of Studio Nicholas Burns recently completed a sweeping concrete chapel and adjoining meditation room, each located on a 30-hectare estate belonging to an ongoing client.

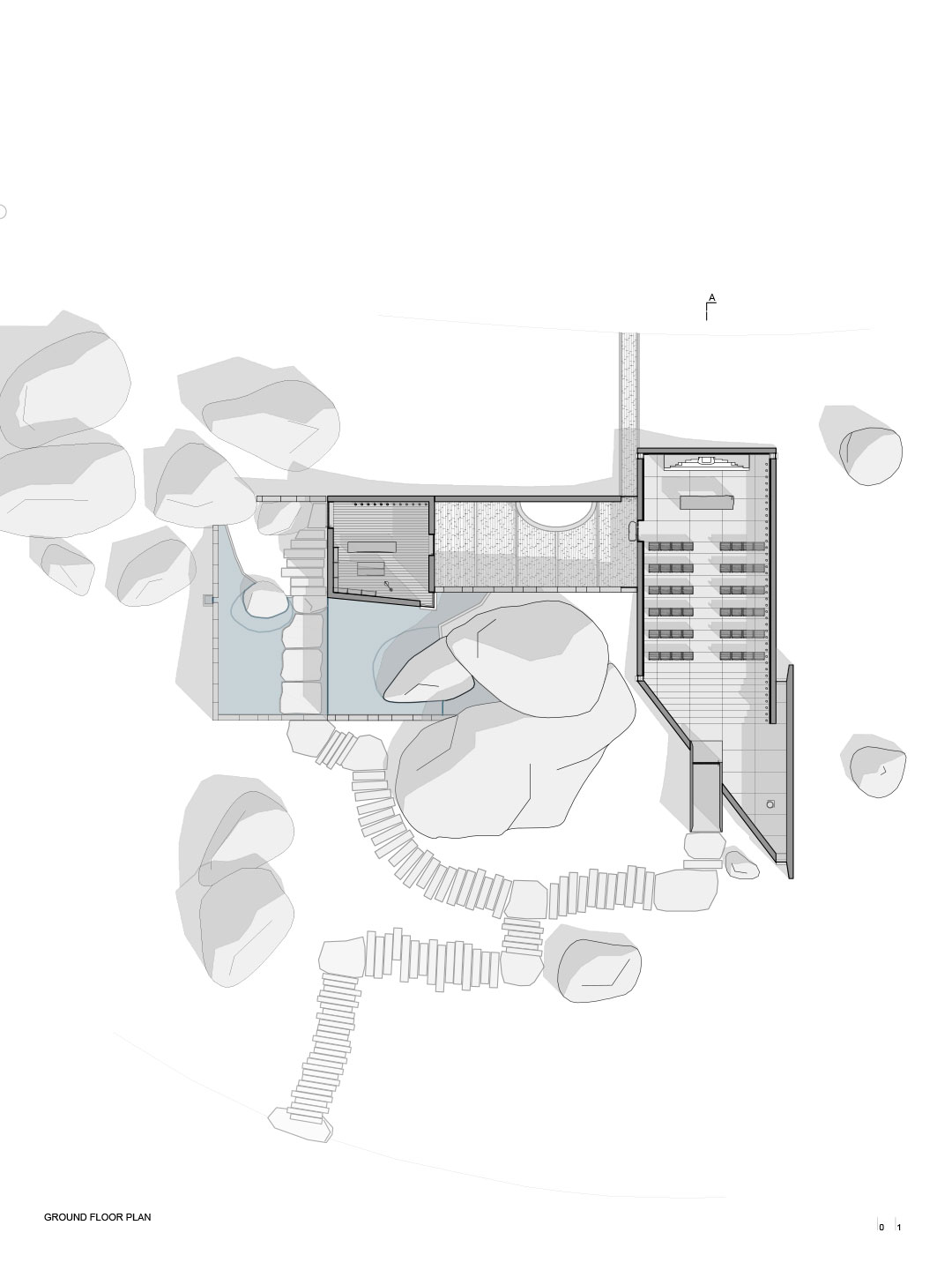

Perched high on a view-framing knoll among handsome boulders covered in luminous lichen and moss, the chapel and meditation room project began with Nicholas “creating spaces within ‘rooms’ in the landscape – without the need to take away from it,” he says. The ‘rooms’ were the spaces that naturally formed between the site’s physical conditions, including the bower of oak trees, scattering of large boulders and native watercourses.

The Chapel and Meditation Room in Portugal by Nicholas Burns Studio

These spaces were partnered with the desired outcomes of enclosure and protection, along with the project’s program, culminating in a pair of buildings that aim to peacefully negotiate with nature. “The design was a response to the site whilst still allowing the function of the building,” says Nicholas.

Certainly the attention-seeker among the project’s two buildings is the chapel whose curved concrete roof shoots up above the treetops towards the clouds, reaching a height that currently seems misguided. But it’s a gesture that will grow into its surrounds as time passes by.

“The height was determined by the height of the trees growing in a few years and becoming taller, concealing the highest point of the building,” Nicholas says. “The landscape will grow around and envelope the building over time and become part of it.”

Another reason for the chapel’s towering volume becomes apparent once visitors step across the building’s threshold. Inside, an imposing gilded-wood altar of baroque origins – owned and restored by the client – adorns the far end of the space, resting at the base of the chapel’s roof peak and completing one component of the project’s multi-layered brief. “I was asked to allow for 60 seats and standing room, space for the 18th century altar, and a meditation room,” says Nicholas.

The chapel’s floorpan and the volumes of various spaces that arise from it make the most of the location’s geographical assets, concealing and revealing light and views along the way. Nicholas used shadow as a “material” in the design of spatial sequences. He also connected interior sightlines with pockets of sky, water and other specific natural elements in order to challenge the concrete building’s relationship with the landscape, encouraging visitors “to feel the spaces,” he says. “[The idea was] to create a space that felt uplifting in a real way, as it squeezes you upwards, allowing an emotive response.”

In a region surrounded by mostly unkempt nature and village architecture, where concrete structures are definitely not the norm, the choice of concrete “made sense,” says Nicholas. “Plasticity was required for the form to flow in between the boulders for the ponds, as well as creating a neutral consistent surface inside and out.”

So while the sinuous concrete surfaces dominate the building’s exterior, they briefly stand aside for Portuguese limestone slabs that run throughout the interior, including along some of the walls and floors. Companioned by blonde-coloured timber furniture, also designed by Studio Nicholas Burns, the tactile limestone contributes a softer mood among the chapel’s hard-edged spaces.

Standing in stark contrast to the chapel, the meditation room is the smaller of the buildings in this partnership. Located off to one side, the humble structure strays from the concrete facade of its larger sibling, calling upon stacked shale to hug its exterior walls. The locally sourced rock forms the base of a deeper material palette and places the meditation room in symphony with the natural surrounds. “The stone and the roughness of the application was intended to allow the building to read more like a landscape and to provide niches for the moss and lichen to inhabit over time, strengthening that notion,” Nicholas says.

Inside the meditation room, the depth of materiality continues. The space is lined floor-to-ceiling with dark-coloured timber, partnered with equally warm timber furnishings. The only relief from the piercing blackness is created by a shard of sunlight that pours into the space through a vertical corner window, which also frames a view toward a boulder “floating” over a pool of water. But once the room’s openings are all sealed off, occupants are left to meditate in the darkness – perhaps by candlelight, perhaps in physical solitude – accompanied only by their thoughts and an unparalleled soundtrack performed by nature.

The stone and the roughness of the application was intended to allow the building to read more like a landscape.

Catch up on more architecture highlights and public spaces, plus subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.

Related stories

- Resa San Mamés student accommodation in Spain by Masquespacio.

- The bar and restaurant at La Sastrería in Valencia by Masquespacio.

- Mama Manana restaurant in Kyiv by Balbek Bureau.

Minho, on the coast of northern Portugal, is a region known for its charming vineyards and river valleys, green-painted fields and a heritage older than the country itself. For it was on these lands that Portugal was founded in 1143. History-rich and immensely fertile, this part of the world is also where Australian-born, Bali-based architect Nicholas Burns of Studio Nicholas Burns recently completed a sweeping concrete chapel and adjoining meditation room, each located on a 30-hectare estate belonging to an ongoing client.

Located near a large lake at the Tervajärvi campground, owned by the parish of Lempäälä, the little timber church was built on an equally small budget. And like most structures of this kind – where funds are sparse – it was pieced together by a dedicated team of volunteers. The available budget was then able to be allocated to highly skilled tradespeople, who were entrusted with the more demanding components of The Forest Chapel project.

The Forest Chapel in Finland by NOAN

The close-knit union formed between the benevolent helpers, professional trades and the principal designers at local architecture firm NOAN, made it possible to explore various design outcomes before realising the building that stands today – one of visually appealing characteristics inspired by the surrounding landscape and ecclesiastical rituals.

The architects viewed the chapel as an interpretation of the evolving role of sacral spaces. “Instead of institutional built symbols and their associated traditions, I see future church buildings as being smaller sacral spaces that emphasise joy and communality, yet also afford consolation,” says Lassi Viitanen, head designer at NOAN.

“The form and proportions of the sacral building should convey the message of a place that provides space for tranquillity,” he adds. “Instead of trying to prophesy what the church in Finland is going to be after 50 years, we should design and build flexible and multifunctional spaces.”

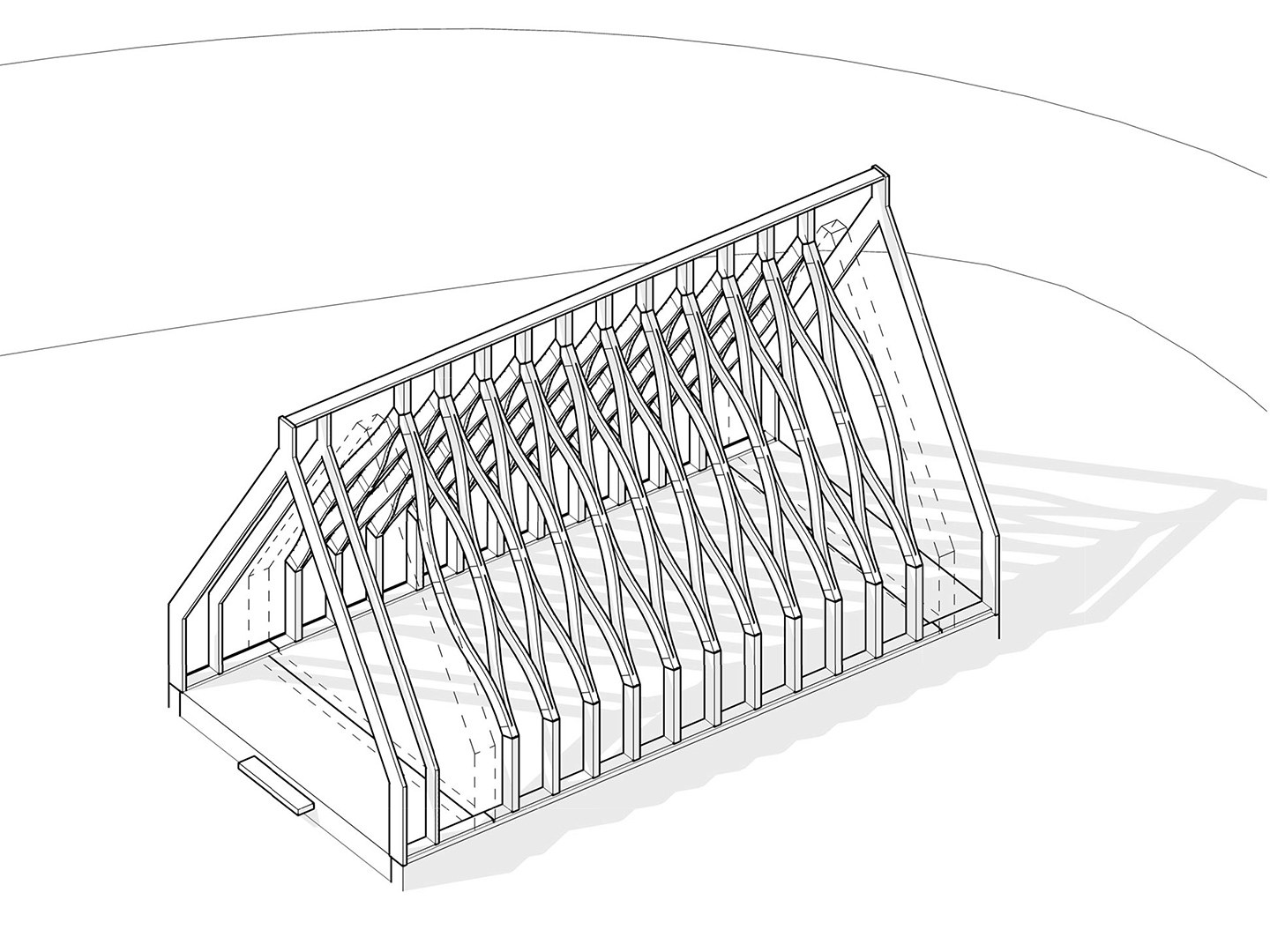

For Lassi, the most important architectural component of the chapel is the glulam timber roof truss. The glulam beam structure plays the main structural role. As such, all the glulam parts (a type of structural engineered timber, in this case using Finnish spruce) arrived at the site prefabricated. These components were manufactured industrially to ensure there was no compromise on precision and finish.

In the final design, the beams of the building curve along the length of the roof, acting as their own diagonal stiffening structure. Since no transverse structures were desired in the relatively small interior space, Lassi explains that the corner joint had to be moment-resisting.

The architects crafted several structural models of the corner joint at a 1:1 scale in order to reach a resolution. “It was difficult to reconcile the appearance, structural function and cost-effective production. This required a lengthy development time with several rounds of comments,” says Lassi. “It took four separate attempts to find the correct shape for the arcs.”

The glulam beam is formed of four 15mm lamellas with a total cross-section of 60 x 240mm. The visible part of the corner joints is a surface lamella that continues along the length of the roof while the structural part is inside the joint: a horizontal section that leads vertical loads downwards. Rotational stiffness of the joints was achieved by placing the screws in a circumferential pattern where the screw holes are concealed by plugs. In fact, no fasteners are visible indoors.

Below the chapel’s enchanting roof structure, the movable Siberian larch furniture – including its brass components – was custom-designed for the building. It was made by local carpenter Puusepänliike Hannes Oy, who collaborated with the architects on resolving the furniture’s joints and other details.

Returning outside, the quaint chapel roof is constructed from grooved planks made of Siberian larch. Here, the roof and exterior surfaces have been treated with tar that has been tinted to a carbon black colour. The roof planks have only been attached in the middle to prevent the wood from cracking as it expands and shrinks with fluctuating moisture levels. And because wood gradually forms a convex curve on its heartwood side, the planks have been laid out with the heartwood upwards to retain water tightness over time.

The underlay of the roof is breathable, the wall and roof structures are permeable to water vapour, and the building is naturally ventilated along the entire roof-top ridge. But The Forest Chapel is not meant to be heated during the wintertime, explains Lassi. “Underfloor heating [only] provides comfort in the chilly early and late summer,” he says.

And so, while The Forest Chapel enters a sort of peaceful hibernation during winter and its flanking months, the space springs to life when the sun eventually pierces through to warm its parishioners. The building then functions as the camp’s on-site church and a location for intimate weddings and christenings during the northern hemisphere’s summertime.

The form and proportions of the sacral building should convey the message of a place that provides space for tranquillity.

Catch up on more architecture highlights and contemporary design, plus subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.