In need of a new HQ, the winemaker from Catalan label Clos Pachem approached the Harquitectes architecture office to provide the solution. But the brief that followed wasn’t quite as straightforward. “The challenge was to allow the winery itself to contribute to the biodynamic winemaking process,” explains the Harquitectes team, who responded to the client’s requests by creating a large pavilion-like structure, connected to the public realm by a zigzagging passageway. The Barcelona-based architects optimised the building’s behaviour based on passive principles “to the greatest possible extent,” they suggest, by harnessing the power of rainwater, airflow and the coolness of the earth.

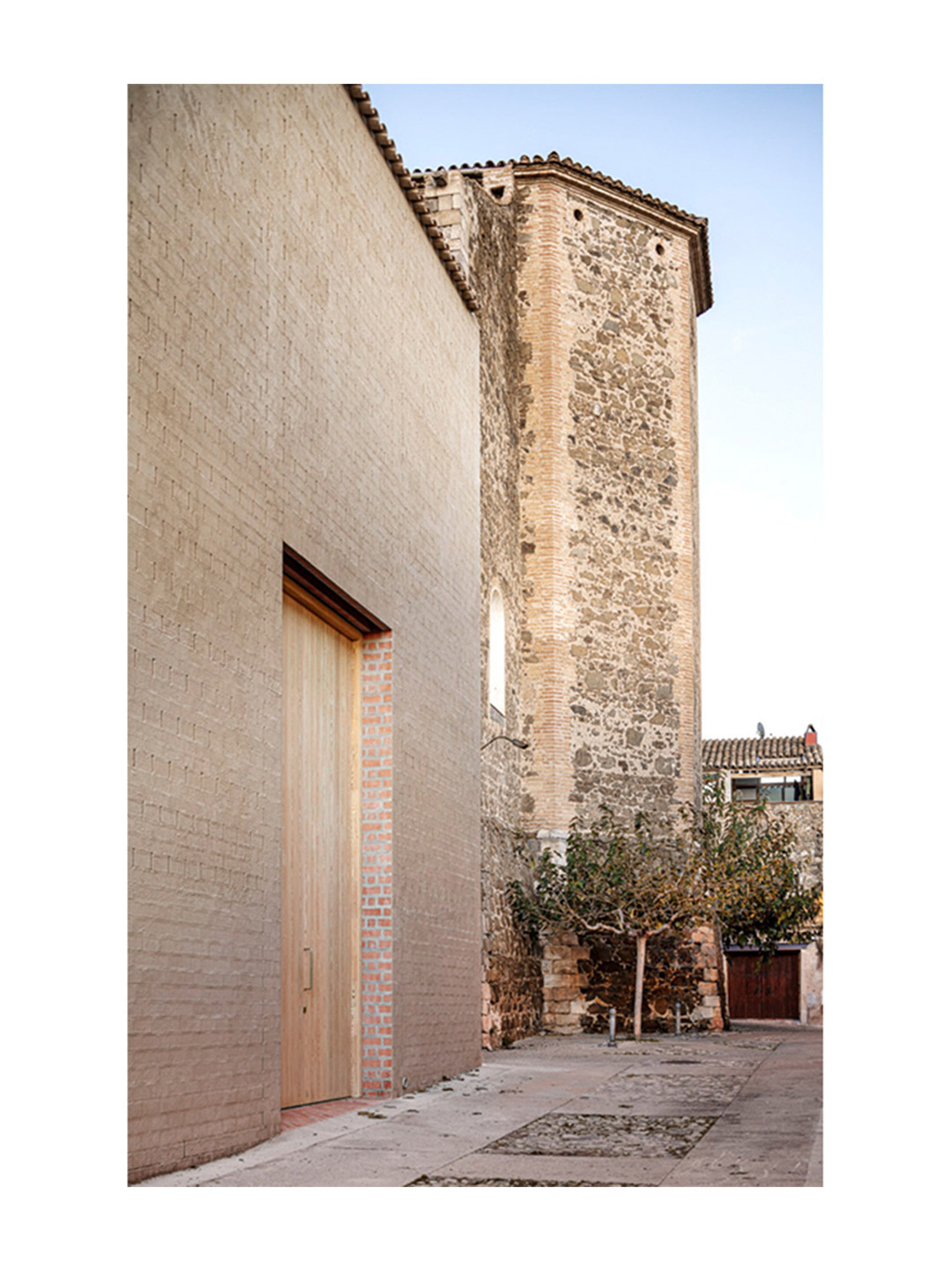

Located in the heart of the historic Gratallops village, in the Priorat region of Spain, the site of the winery traces the form of an L-shaped polygon. It’s hugged closely on its sides by narrow laneways and traditional row houses, and overlooked by the nearby church – the town’s most dominant structure. The site boundary is marked by an old stone wall – a former handball structure rising to 10 meters at one point – which follows an irregular line. The geometry of this wall (an amalgam of stone, brick and plaster rendering) became the starting point for the Clos Pachem project.

Clos Pachem Winery in Spain by Harquitectes

When overlaid with the area’s planning regulations, the client’s desire to build the biggest possible structure on the site led the architects to design two distinct zones. The first space is a large volume on a regular-shaped plan, as wide and high as allowed, designated to the task of winemaking. This is joined by the Z-shaped zone – nicknamed “the passage” by the architects – where the smaller spaces around the pavilion are gathered and put to use, extending like an inner lane that follows the geometry of the boundary wall. The passage performs as the main entrance to the precinct, and as a circulation and reception space for visitors and wine-tasting groups.

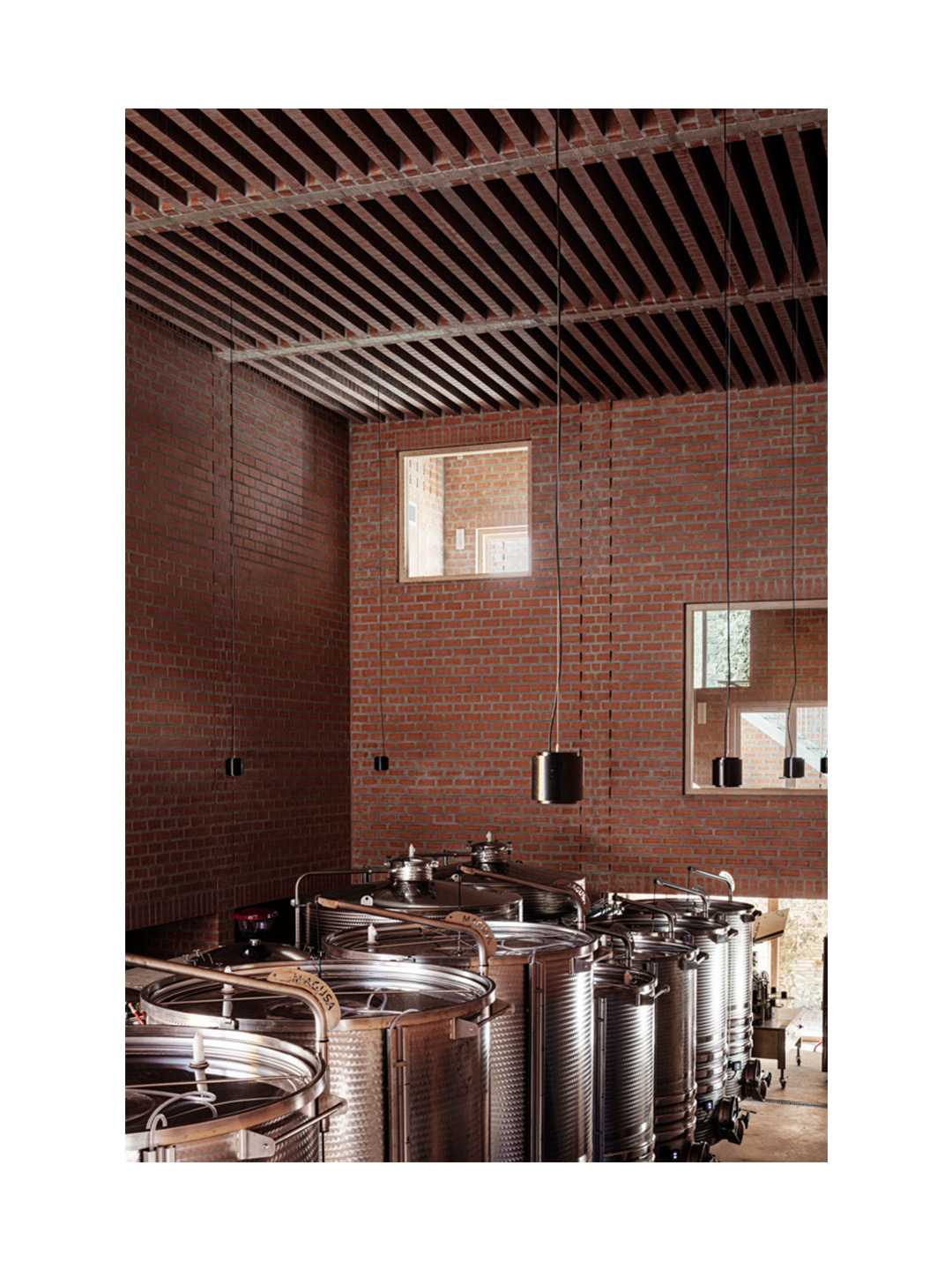

The interior of the central pavilion (where the wine fermentation vats are located) stretches to a height of three storeys. “This is the heart of the project, the space that really defines the winery,” say the Harquitectes team. “All the other spaces are articulated around it,” they add. The pavilion captures a large volume of fresh air, insulated by deep walls that measure up to 1.75 metres thick. It’s kept cool by a system of load-bearing brick walls in multiple layers set between pilasters, generating pockets of circulating air between the walls.

Small rooms within the large walls contain the winery’s complementary activities. Including on the ground floor, where a series of “chapel-like cavities” follow the rhythm of the structural pilasters around the perimeter of the central space. These spaces visually connect the building to the passage but also facilitate the manoeuvring and storage of machinery required in the winemaking cellar. Looking upwards, the nave is dark and dense, while on the ground floor, it expands, opening to the light in the passage; the place where both grapes and visitors are received.

This partially outdoor route follows a succession of roofs with different heights, combined with concrete slabs that form broad landings between the staircases. Rainwater falls and collects on the slabs (that have been transformed into green roofs) until it spills over from one to the next, descending ever more slowly as it flows through the passage. “[This helps] freshen the atmosphere and water the vegetation along the way,” the architects explain. From underneath, the slabs provide visitors with shelter from the rain. But they also block direct sunlight, creating a cool ambiance for the passage, “like a terraced garden,” the architects suggest, “where an outdoor tavern can be installed for wine sales, tastings and snacks”.

The most technologically demanding spaces – the barrel zone and the storeroom for bottled wine – require a perfectly stable moisture and temperature regime. For this reason, they are located in the basement, in direct contact with the earth. “The major challenge, however, is the vinification hall, with equally demanding thermal requirements that must be fulfilled without interaction with the ground,” the architects say. They resolved this with a two-part strategy. Firstly, by generating the greatest possible interior height to facilitate the stratification of the warm air at the top, away from the barrels. “Secondly, the hydrothermal stability of the interior is aided by maximising the inertia of the building systems,” the architects explain.

Another bioclimatic strategy is in action on the roof, whose central part is a cooling device that employs radiation from the night sky to refrigerate the floor slab. This device is made up of a closed-circuit water-cycling system that runs between two levels. The upper level provides contact with the outdoor environment, where water is used at night as a heat transfer fluid to dissipate the indoor ambient warmth. And the lower level is in contact with the floor, where a feeling of freshness is transferred to the interior. “This large-scale exchange between the pavilion’s interior and the temperature of the universe, through radiation, is an inexhaustible refrigeration source,” the architects explain.

Returning to the street, the facade of the Clos Pachem winery is capped with tiles and clad with a thin layer of lime mortar, which helps contextualise the building in the village setting and clearly differentiate its external materiality from the interior passageway. “Viewed from the outside, the building has a somewhat vernacular presence,” the architects suggest. “But as one enters the corridor, the building systems become deconstructed and slowly reveal the nature of the complex.”

Viewed from the outside, the building has a somewhat vernacular presence. But as one enters the corridor, the building systems become deconstructed.

Catch up on more architecture, art and design highlights. Plus, subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.