During the depths of winter in southern Finland, The Forest Chapel, known locally as Metsäkappeli, is only distinguishable by its gable-shaped faces peering out from underneath a blanket of snow. The black tar-coated timber of the chapel’s north and south elevations commands attention against the pure white ice. But when the snow melts and the forest begins to reawaken in the spring, a humble example of temple architecture stands quietly among the woodlands.

Located near a large lake at the Tervajärvi campground, owned by the parish of Lempäälä, the little timber church was built on an equally small budget. And like most structures of this kind – where funds are sparse – it was pieced together by a dedicated team of volunteers. The available budget was then able to be allocated to highly skilled tradespeople, who were entrusted with the more demanding components of The Forest Chapel project.

The Forest Chapel in Finland by NOAN

The close-knit union formed between the benevolent helpers, professional trades and the principal designers at local architecture firm NOAN, made it possible to explore various design outcomes before realising the building that stands today – one of visually appealing characteristics inspired by the surrounding landscape and ecclesiastical rituals.

The architects viewed the chapel as an interpretation of the evolving role of sacral spaces. “Instead of institutional built symbols and their associated traditions, I see future church buildings as being smaller sacral spaces that emphasise joy and communality, yet also afford consolation,” says Lassi Viitanen, head designer at NOAN.

“The form and proportions of the sacral building should convey the message of a place that provides space for tranquillity,” he adds. “Instead of trying to prophesy what the church in Finland is going to be after 50 years, we should design and build flexible and multifunctional spaces.”

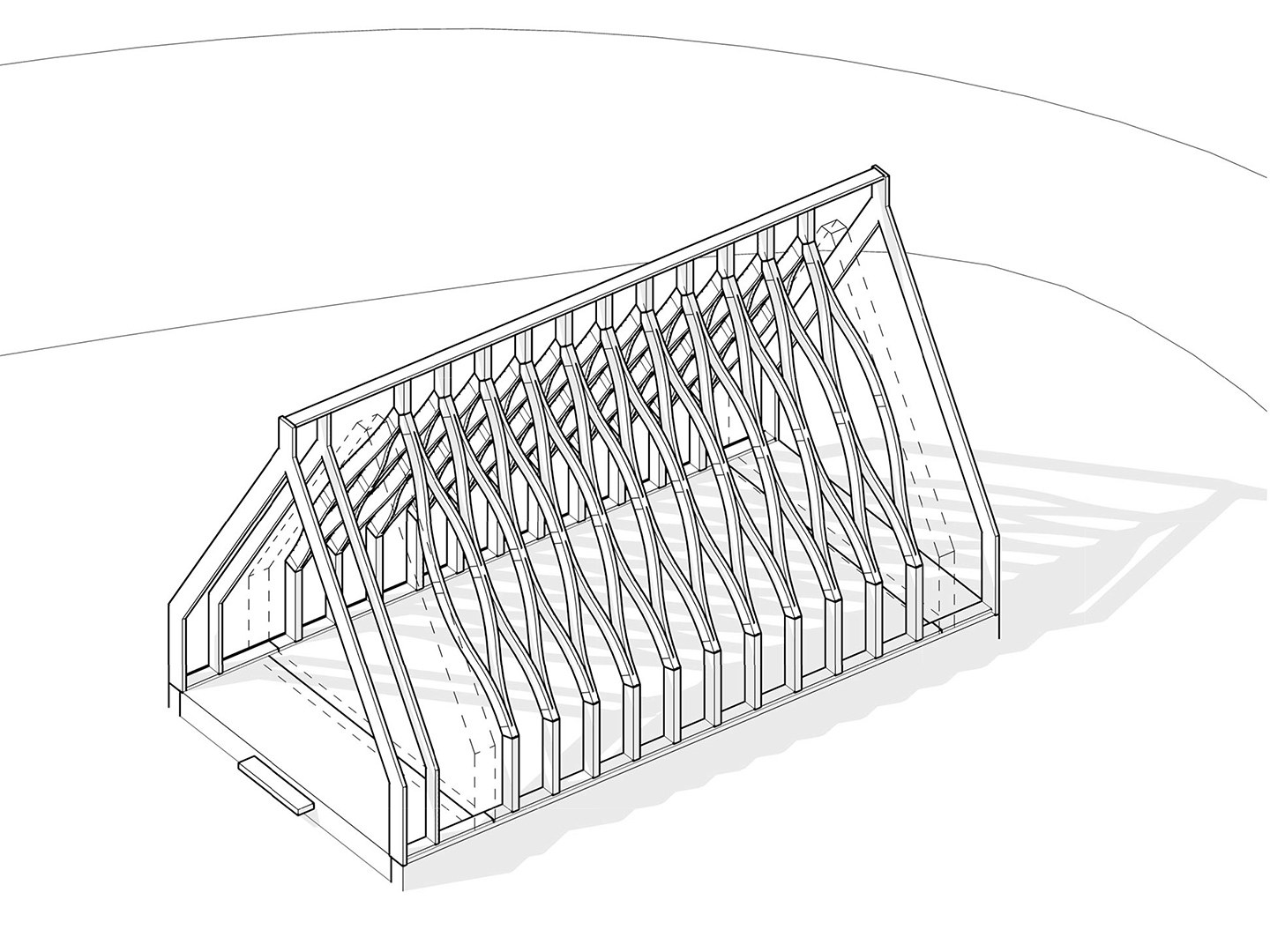

For Lassi, the most important architectural component of the chapel is the glulam timber roof truss. The glulam beam structure plays the main structural role. As such, all the glulam parts (a type of structural engineered timber, in this case using Finnish spruce) arrived at the site prefabricated. These components were manufactured industrially to ensure there was no compromise on precision and finish.

In the final design, the beams of the building curve along the length of the roof, acting as their own diagonal stiffening structure. Since no transverse structures were desired in the relatively small interior space, Lassi explains that the corner joint had to be moment-resisting.

The architects crafted several structural models of the corner joint at a 1:1 scale in order to reach a resolution. “It was difficult to reconcile the appearance, structural function and cost-effective production. This required a lengthy development time with several rounds of comments,” says Lassi. “It took four separate attempts to find the correct shape for the arcs.”

The glulam beam is formed of four 15mm lamellas with a total cross-section of 60 x 240mm. The visible part of the corner joints is a surface lamella that continues along the length of the roof while the structural part is inside the joint: a horizontal section that leads vertical loads downwards. Rotational stiffness of the joints was achieved by placing the screws in a circumferential pattern where the screw holes are concealed by plugs. In fact, no fasteners are visible indoors.

Below the chapel’s enchanting roof structure, the movable Siberian larch furniture – including its brass components – was custom-designed for the building. It was made by local carpenter Puusepänliike Hannes Oy, who collaborated with the architects on resolving the furniture’s joints and other details.

Returning outside, the quaint chapel roof is constructed from grooved planks made of Siberian larch. Here, the roof and exterior surfaces have been treated with tar that has been tinted to a carbon black colour. The roof planks have only been attached in the middle to prevent the wood from cracking as it expands and shrinks with fluctuating moisture levels. And because wood gradually forms a convex curve on its heartwood side, the planks have been laid out with the heartwood upwards to retain water tightness over time.

The underlay of the roof is breathable, the wall and roof structures are permeable to water vapour, and the building is naturally ventilated along the entire roof-top ridge. But The Forest Chapel is not meant to be heated during the wintertime, explains Lassi. “Underfloor heating [only] provides comfort in the chilly early and late summer,” he says.

And so, while The Forest Chapel enters a sort of peaceful hibernation during winter and its flanking months, the space springs to life when the sun eventually pierces through to warm its parishioners. The building then functions as the camp’s on-site church and a location for intimate weddings and christenings during the northern hemisphere’s summertime.

The form and proportions of the sacral building should convey the message of a place that provides space for tranquillity.

Catch up on more architecture highlights and contemporary design, plus subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.