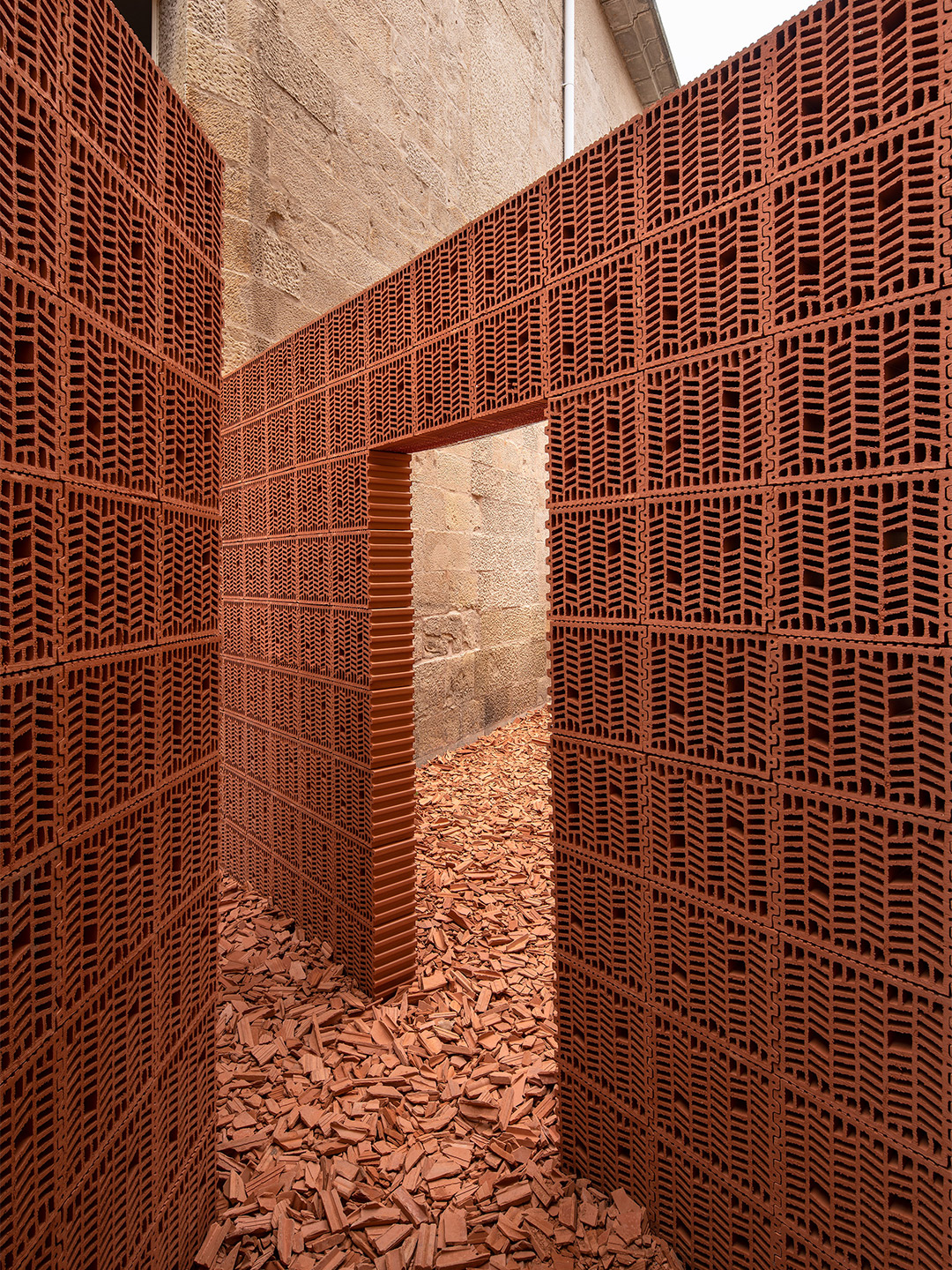

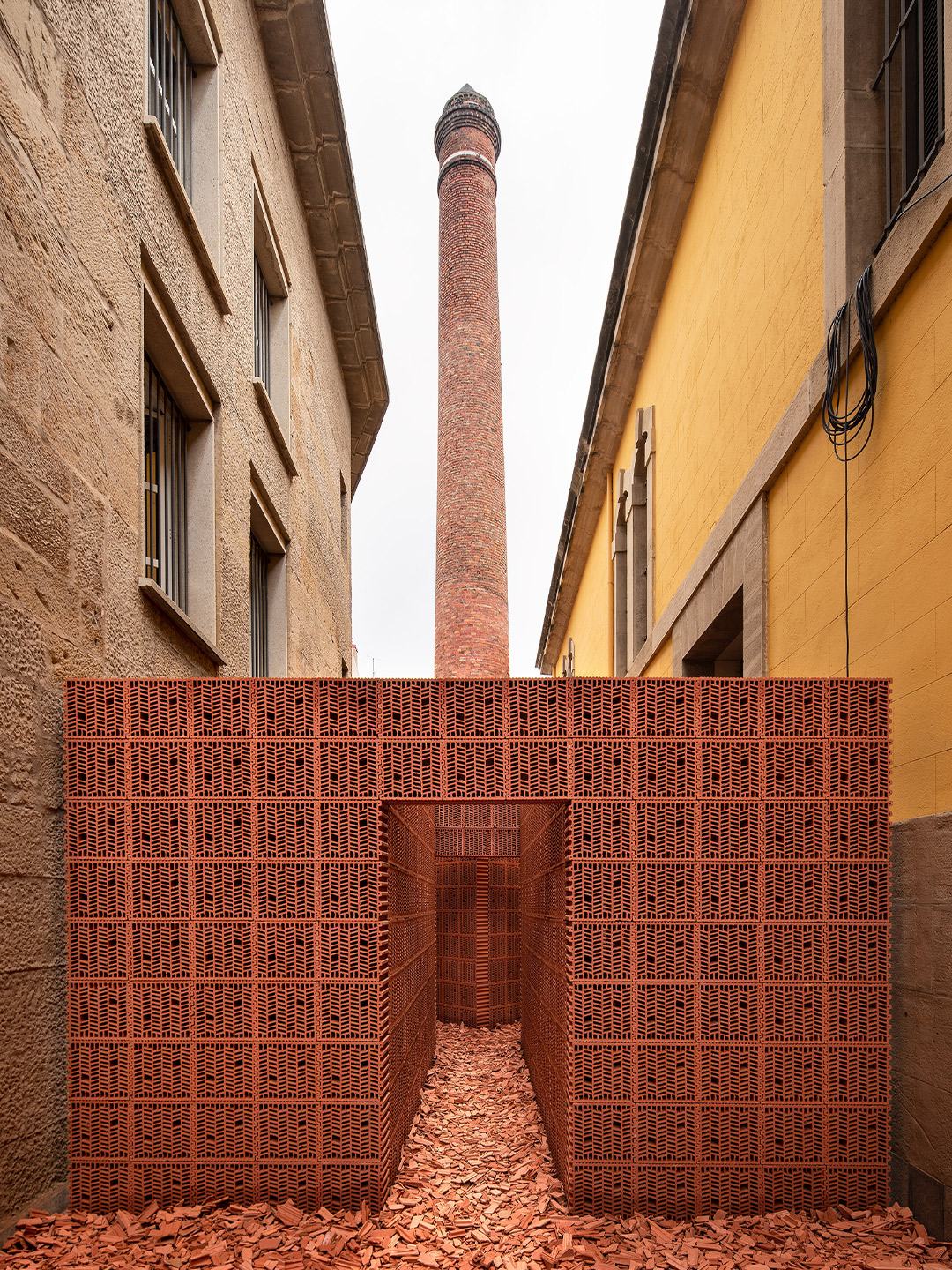

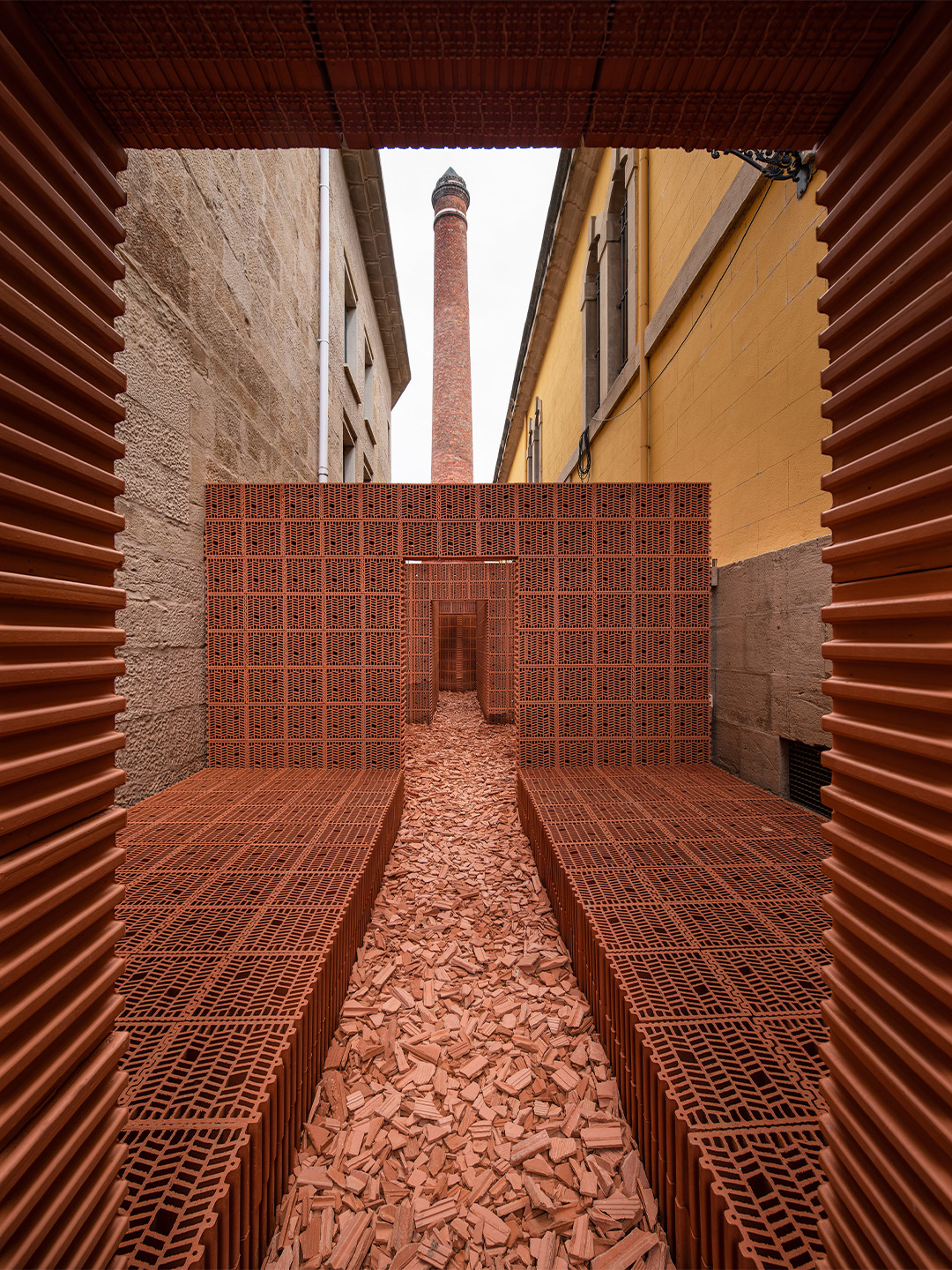

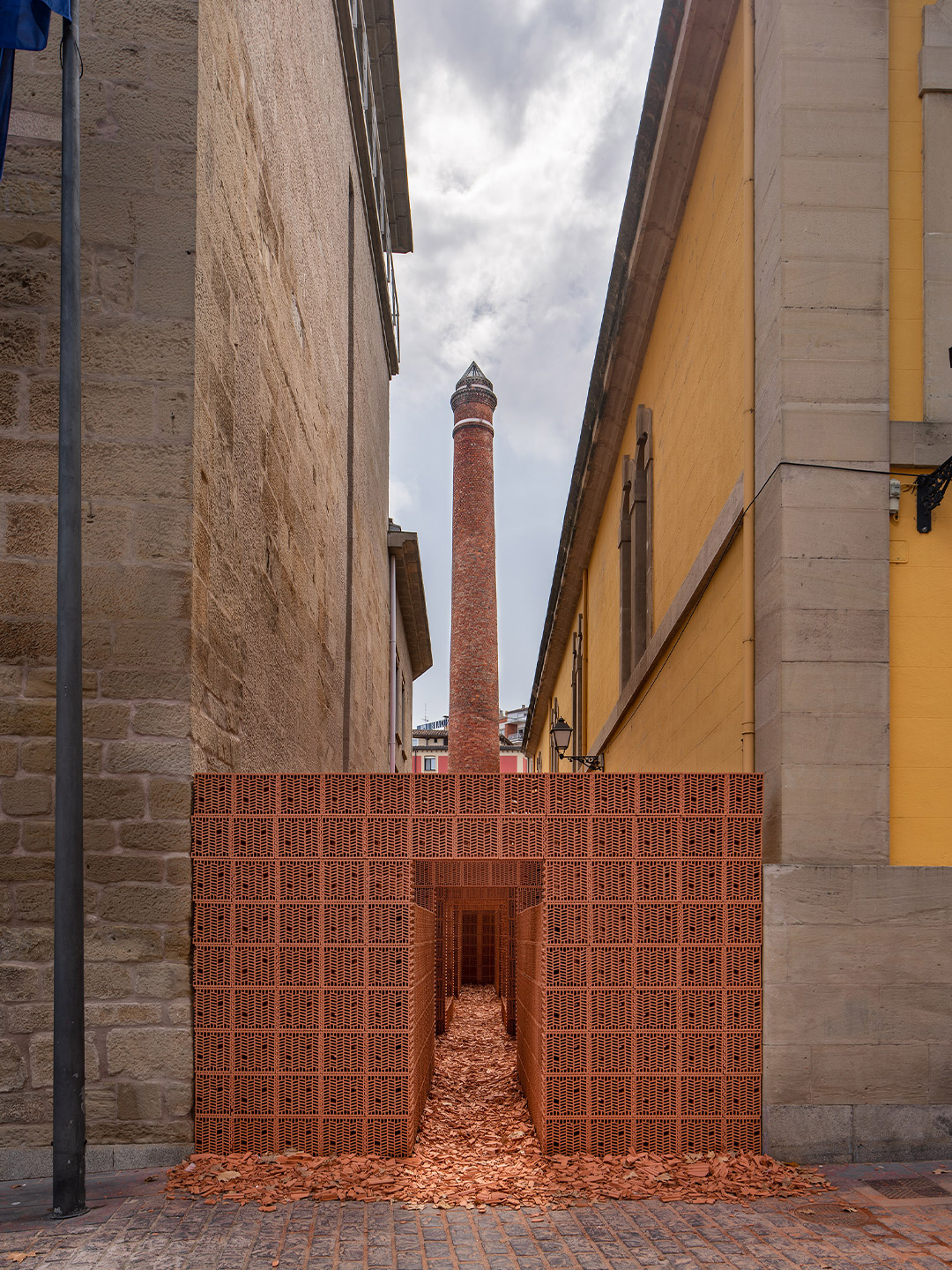

In early September, visitors who strolled down the laneway leading to the historic tobacco factory of La Rioja in Spain were confronted by a new experience – albeit one that played on notions of familiarity. Overlooked by the factory’s imposing red-brick chimney, the narrow space that trails between two buildings was filled with a procession of small corridors and rooms that mimicked the volumes of a typical house. Set within a grid of 3.6-metre squares, the rooms were traced out by domestic-scaled walls, put together with interlocking terracotta-coloured bricks that appeared to glow in the warm autumn sun.

Given the name Tipos de Espacio (translating to ‘Types of Spaces’), the temporary exhibit was created by two design offices, Palma from Mexico and Madrid-based HANGHAR, for the duration of Concéntrico, the international architecture and design festival of Logroño. This year marked the seventh edition of Concéntrico in Logroño, the capital of La Rioja, and Types of Spaces was just one of the many highlights that continued the festival’s mission: to form a dialogue between the city, its heritage and the rise of contemporary architecture.

‘Types of Spaces’: a temporary exhibit in the Spanish city of Logroño by Palma + HANGHAR

Since its inception in 2015, the ambitious festival has invited visitors to experience the city through installations, discussions, activities and exhibitions that pull focus on public space and places of coexistence – a theme that’s all the more relevant during pandemic times. Each year the guest designers place particular emphasis on the sustainability of the materials and processes they use in their presentations.

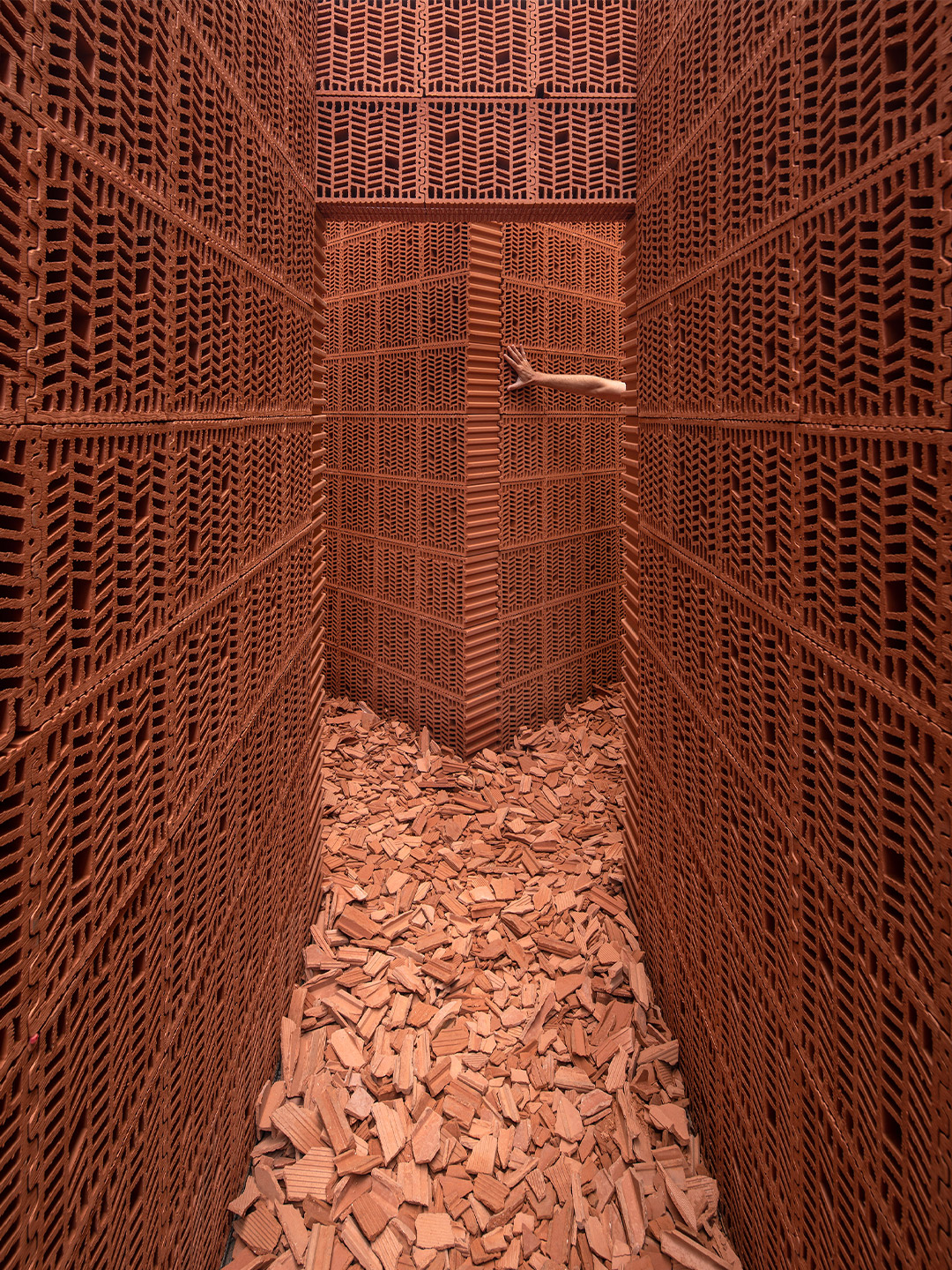

With its roof-less rooms, the Types of Spaces exhibit was tasked with exploring various spatial possibilities through the “emphatic geometries” of its plan. The domestic scale of the rooms, described by the designers as feeling “alien” in the public realm, was intended to transform the occupant from casual visitor to inhabitant. Acting as a reminder of the exposed nature of the intervention, a light water mist was sprayed on guests intermittently. “This allowed a more profound interaction with the installation,” the design team say.

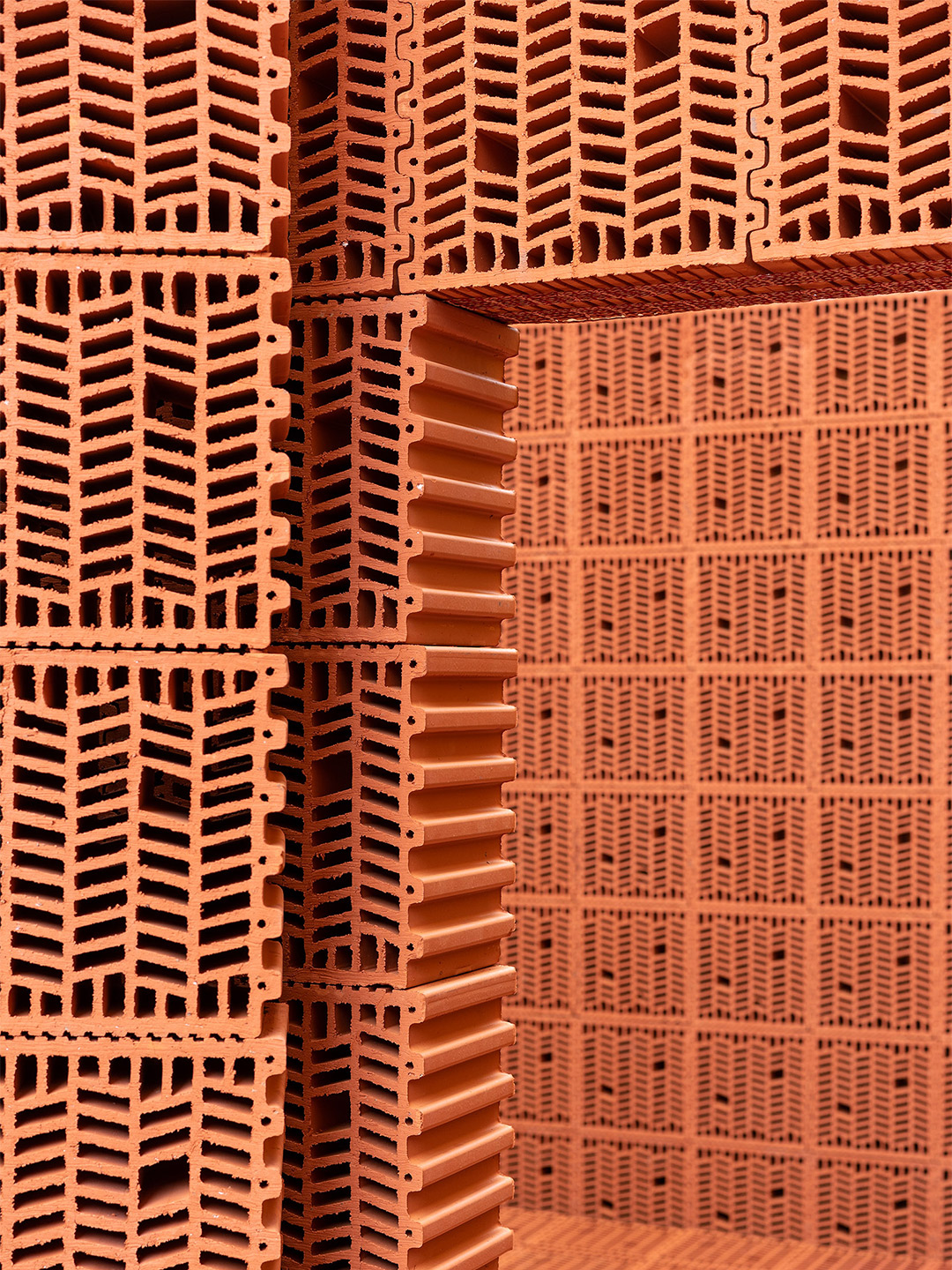

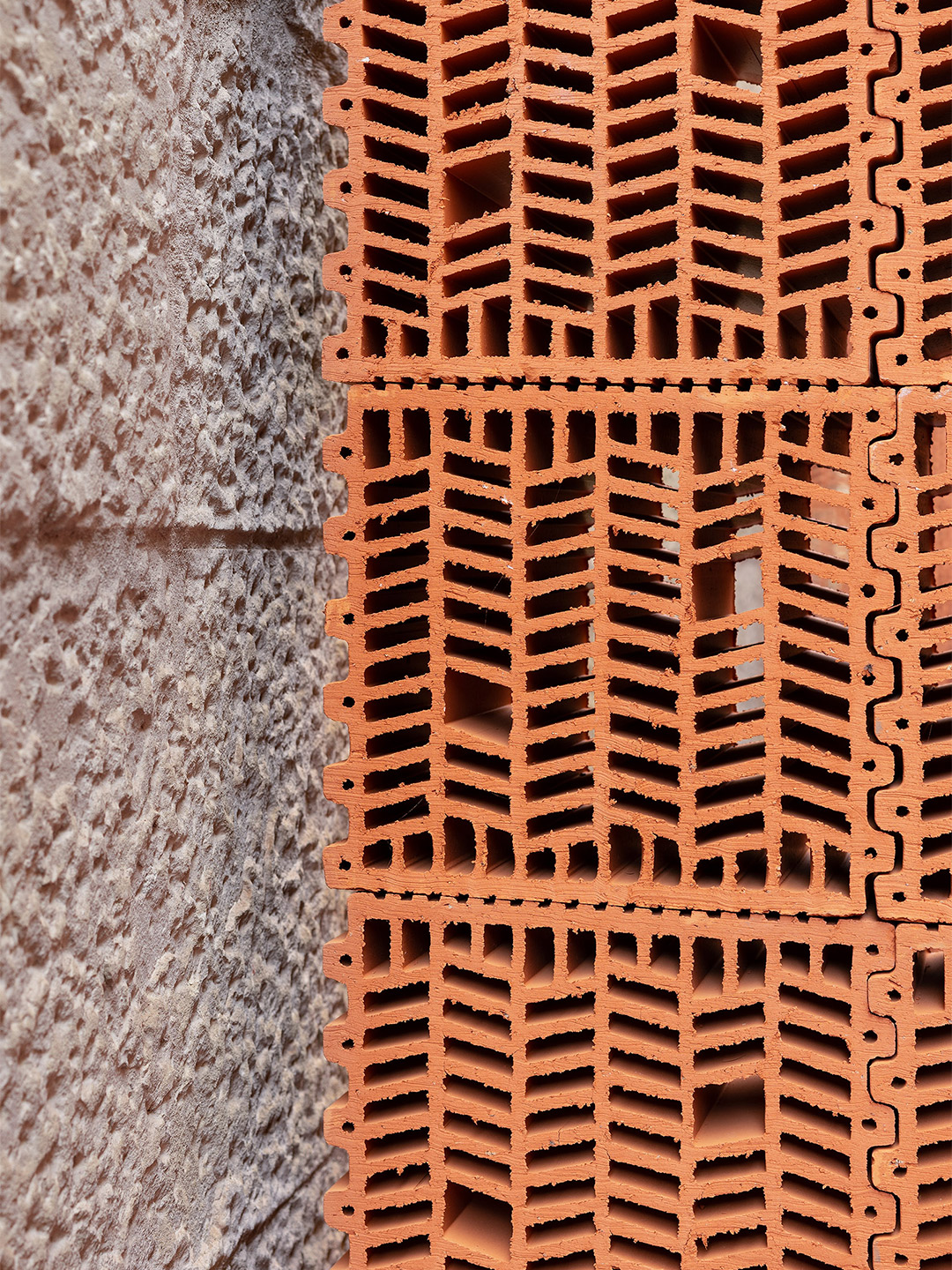

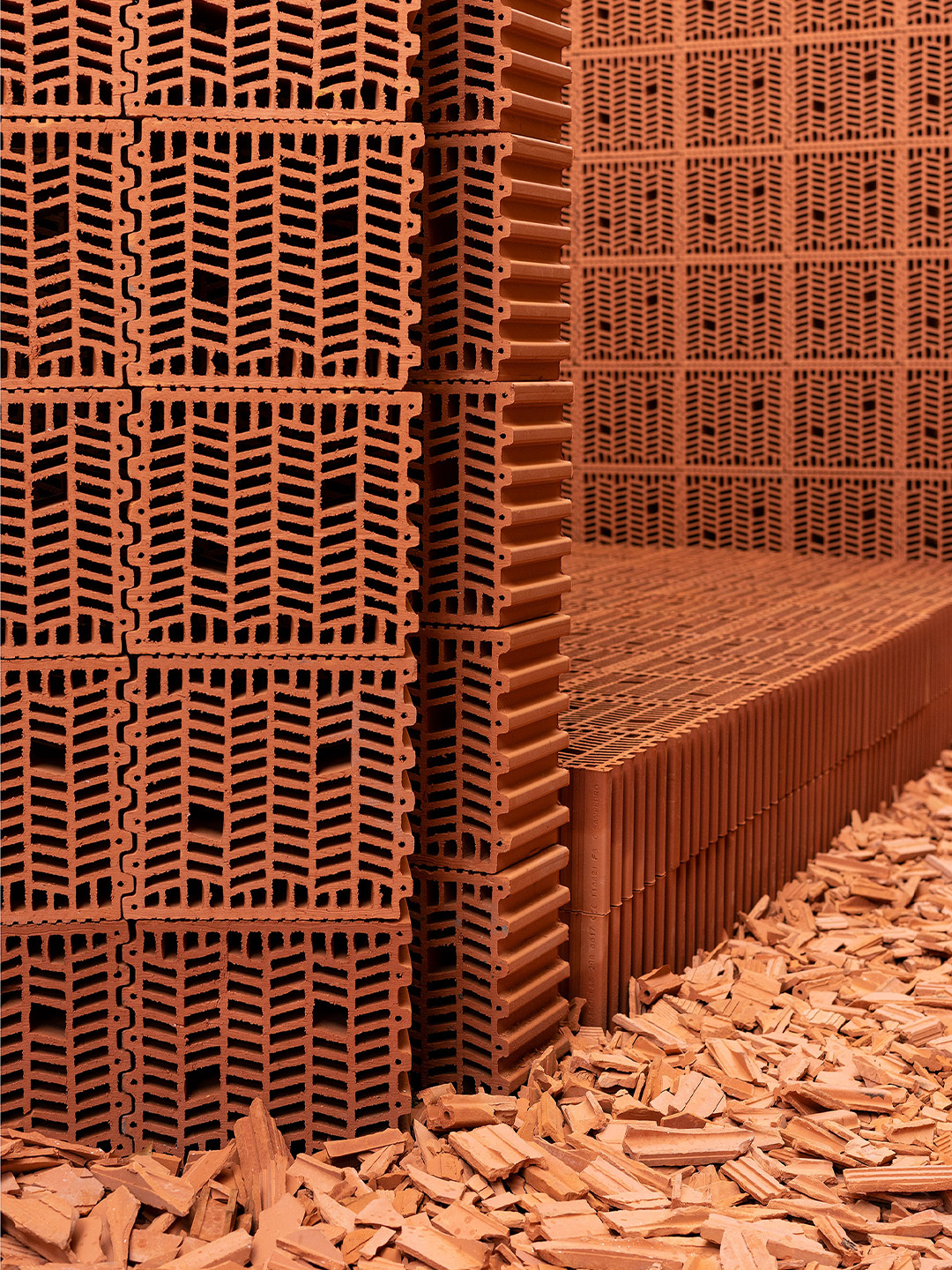

The “programmatically generic but spatially specific” areas of the installation were built with square-format thermo-clay bricks. When combined with the scale of the volumes, this everyday material gave the project its visually familiar condition. “Moreover, the brick block is both the material and spatial unit of the project,” the designers explain. They add that the bricks generated a system “with a stereotomic appearance capable of veiling its tectonic logic” which they say was made possible by the “massiveness” of the 300mm-square pieces.

The floor of the installation, carpeted with broken pieces of discarded bricks, gave the exhibit a sense of material continuity. But the gentle crunchiness underfoot was also a way to slow down the walking pace of those who passed through, allowing them more time to consider an often overlooked part of Logroño, and enjoy the experience “away from the hustle and bustle of the city,” the designers conclude.

palma-mx.com; hanghar.com; concentrico.es

The domestic scale of the rooms, described by the designers as “alien” in the public realm, was intended to transform the occupant from casual visitor to inhabitant.

Catch up on more architecture, art and design highlights. Plus, subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox each week.

Related stories

- Adam Goodrum stamps all-Australian style on new breezeblock design.

- Bitossi celebrates centenary in Florence with new museum and 7000-piece display.

- Casa R+1 residence in southern Spain by Puntofilipino.

In the south of France, Cinéma Le Grand Palais is a new addition to the historic village of Cahors. Located to the north of the township’s centre, just a few steps away from the banks of the magnificent Lot River, the cinema complex joins a precinct with a storied past; an ensemble of buildings that were originally used as a convent, then later employed as a military base. After a fire in 1943 left the east wing of the complex in ashes, the then vacant space between the remaining buildings – now the site of the cinema – became a poorly defined parking lot.

When designing Cinéma Le Grand Palais, the team from Antonio Virga Architects looked to the existing buildings and their surrounds for inspiration. In particular, a commonality that was shared between each of the structures on-site. “All of the buildings were organised according to a rigorous set of planning rules, in accordance with 19th-century design practices for military and public facilities,” say the architects. To properly restore the scale of this ensemble, where the new cinema filled a long overlooked void, the group of spaces was treated with “great simplicity,” they add. “With a coherent choice of materials, furniture and plantations.”

Cinéma Le Grand Palais in Cahors by Antonio Virga Architects

Taking full advantage of the existing elements, such as the buildings, trees and sightlines, the architects reveal that the basis of the project was to find the “lost urbanicity” that the site once had or could have. They explain: “It was important to have a timeless architectural expression, so that [the cinema] would not stand as just something new in the old, but as something that would connect strongly with the existing, maybe as if it had been there for a long time – avoiding all pastiche or faux vieux.”

To achieve this sense of understated newness, the brick volume of the cinema mirrors the volumes of the existing buildings, reinterpreting their materiality with new-generation masonry products. “We wanted to use a material that would blend well with the materials of old Cahors,” say the architects. Brick is commonly used in the traditional architecture of Cahors – visible, for example, on the facade of the nearby church of Saint Barthelemy – and thus functions as an obvious link between the new architecture of the cinema and that of the old town.

“We also chose a [brick] colour that is reminiscent of the natural stone of Cahors,” the architects add. Again, this was something new that was sympathetic to the existing architectural fabric, yet it gave the building a contemporary edge. Especially in the way the pale-coloured bricks were put to use with patches of perforated brickwork replacing standard windows. “The building was designed as a virtually windowless volume, all covered in brick – including its roof,” the team say. “We wanted to use this traditional material in an inventive and surprising way.”

The desired program of Le Grand Palais (a cinema with seven rooms) was always going to be larger than the area made possible within the brick building, so the team at Antonio Virga Architects needed to make it bigger. This was achieved via a glimmering gold-panelled annexe. “To not lose the symmetry created by copying the older buildings, we opted for this false extension,” the architects explain. “A second building [wrapped] in golden metal – a material that, again, blends well with the colours of Cahors.” Just like the brick building, the so-called “false extension” is a totally new structure. It’s considered by the architects to be “more flagrant” than the first, but it’s also more hidden from certain viewpoints, positioning the cinema complex as an architectural jewel and cultural gem just waiting to be discovered.

It was important to have a timeless architectural expression … maybe as if it had been there for a long time.

Catch up on more architecture, art and design highlights. Plus, subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.

Related stories

- Venus Power collection of rugs by Patricia Urquiola for cc-tapis.

- Bitossi celebrates centenary in Florence with new museum and 7000-piece display.

- Casa R+1 residence in southern Spain by Puntofilipino.

Beyond its sinuous facade comprising an ornate veil clad with terracotta bricks and glazed ceramic blocks, Gallery House in Bansberia – a peri-urban locale in India’s West Bengal – proudly serves the community in more ways than one. By day, the two-level concrete-framed building acts as a gallery, gathering space and multi-purpose centre, offering local residents the opportunity to partake in activities ranging from education sessions to yoga classes. “At night, this space functions as a dormitory for resident staff,” says principal designer Abin Chaudhuri of Abin Design Studio (ADS), whose client “enjoys a sense of pride and joy of ownership seeing the space put to good use.”

But the small parcel of land wasn’t always intended to be charged with such noble pursuits. The designers were originally briefed to devise a car parking structure, with staff quarters above, directly across the road from the home they created for the same client. “Given its simple program, ADS convinced the client to use this opportunity for doing a lot more and to think of how it could give back to the community,” says Abin. Inspired by the potential of the plot, the owner decided to let go of the garage component of the initial brief and embraced the designer’s suggestion of presenting the ground floor as a community-focussed facility. The program of the building’s upper floor was expanded to house a multi-purpose room, sitting area, bathrooms and a small kitchen.

Through its reinterpretation of Bengal’s decorative terracotta temples, such as the 200-year-old temple of Ananta Basudeva, the facade of Gallery House introduces a new sense of architectural expression to the local landscape. The designers sourced the terracotta bricks of varying shapes and sizes “from a riverside brick field located nearby,” Abin says, while the inlaid ceramic blocks were salvaged from the seconds piles of nearby manufacturers. “These two [materials] were combined using the locally prevalent finesse of building with masonry,” he adds. The bricks and blocks were brought together in a mesmerising patchwork created in collaboration with ceramic artist Partha Dasgupta.

Every year, as part of a cultural celebration, the neighbourhood that surrounds Gallery House holds a colourful procession that weaves its way through the narrow lanes of Bansberia. In response to this much-anticipated occasion, the building steps down towards the street forming a concrete amphitheatre-like arrangement where onlookers can sit, socialise and view the event. At other times, the concrete stairs spilling from the ground-floor gallery form a gathering spot that further contributes to the building’s new-found mission to support the neighbourhood: “a humane gesture of giving back to the local community,” Abin says.

Catch up on more residential designs and the latest architecture highlights, plus subscribe to the Daily Architecture News e-letter to receive weekly updates direct to your inbox.

The client enjoys a sense of pride and joy of ownership seeing the space put to good use.