WATCH: Global architecture highlights including the Chapel and Meditation Room.

Minho, on the coast of northern Portugal, is a region known for its charming vineyards and river valleys, green-painted fields and a heritage older than the country itself. For it was on these lands that Portugal was founded in 1143. History-rich and immensely fertile, this part of the world is also where Australian-born, Bali-based architect Nicholas Burns of Studio Nicholas Burns recently completed a sweeping concrete chapel and adjoining meditation room, each located on a 30-hectare estate belonging to an ongoing client.

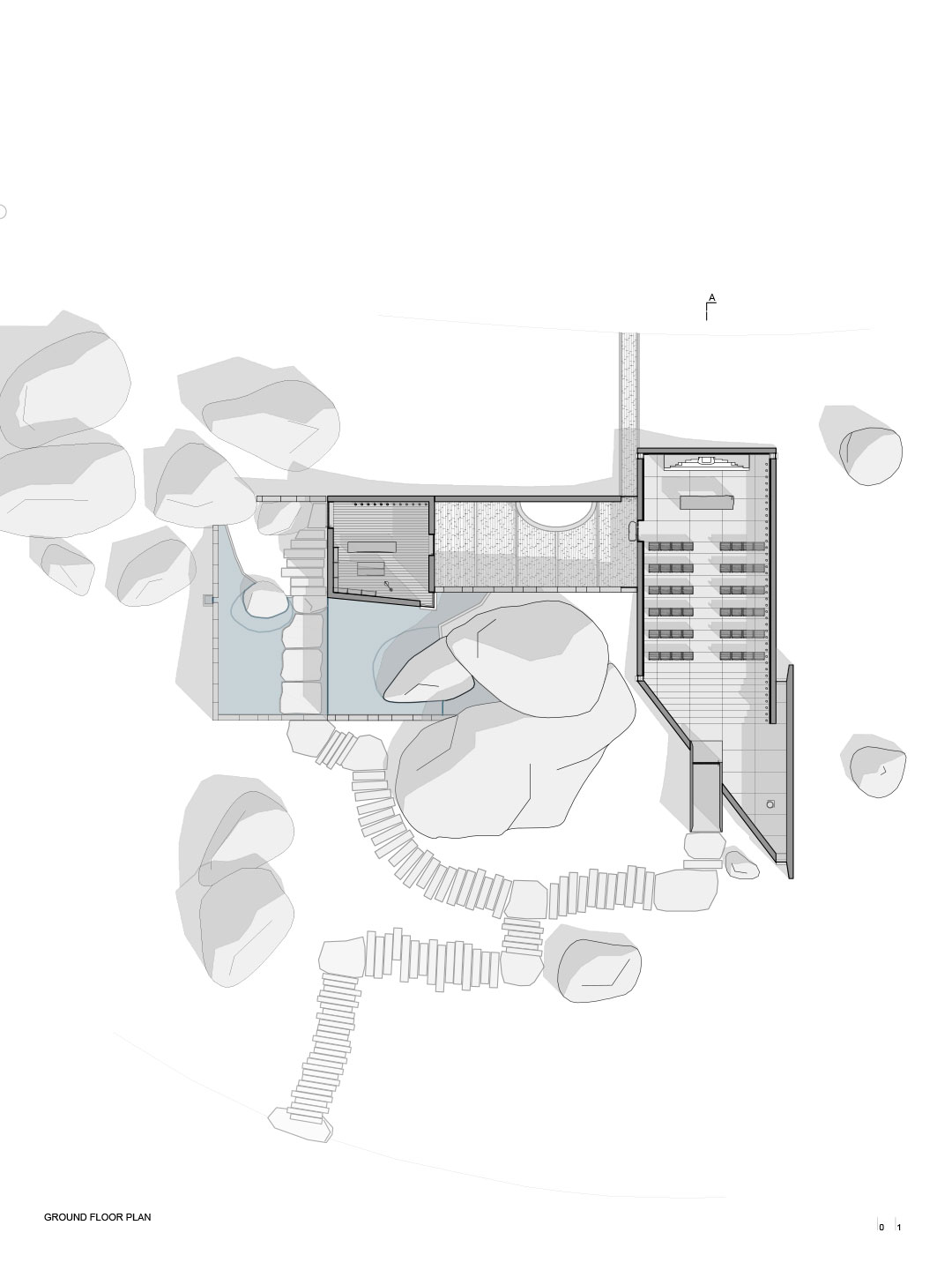

Perched high on a view-framing knoll among handsome boulders covered in luminous lichen and moss, the chapel and meditation room project began with Nicholas “creating spaces within ‘rooms’ in the landscape – without the need to take away from it,” he says. The ‘rooms’ were the spaces that naturally formed between the site’s physical conditions, including the bower of oak trees, scattering of large boulders and native watercourses.

The Chapel and Meditation Room in Portugal by Nicholas Burns Studio

These spaces were partnered with the desired outcomes of enclosure and protection, along with the project’s program, culminating in a pair of buildings that aim to peacefully negotiate with nature. “The design was a response to the site whilst still allowing the function of the building,” says Nicholas.

Certainly the attention-seeker among the project’s two buildings is the chapel whose curved concrete roof shoots up above the treetops towards the clouds, reaching a height that currently seems misguided. But it’s a gesture that will grow into its surrounds as time passes by.

“The height was determined by the height of the trees growing in a few years and becoming taller, concealing the highest point of the building,” Nicholas says. “The landscape will grow around and envelope the building over time and become part of it.”

Another reason for the chapel’s towering volume becomes apparent once visitors step across the building’s threshold. Inside, an imposing gilded-wood altar of baroque origins – owned and restored by the client – adorns the far end of the space, resting at the base of the chapel’s roof peak and completing one component of the project’s multi-layered brief. “I was asked to allow for 60 seats and standing room, space for the 18th century altar, and a meditation room,” says Nicholas.

The chapel’s floorpan and the volumes of various spaces that arise from it make the most of the location’s geographical assets, concealing and revealing light and views along the way. Nicholas used shadow as a “material” in the design of spatial sequences. He also connected interior sightlines with pockets of sky, water and other specific natural elements in order to challenge the concrete building’s relationship with the landscape, encouraging visitors “to feel the spaces,” he says. “[The idea was] to create a space that felt uplifting in a real way, as it squeezes you upwards, allowing an emotive response.”

In a region surrounded by mostly unkempt nature and village architecture, where concrete structures are definitely not the norm, the choice of concrete “made sense,” says Nicholas. “Plasticity was required for the form to flow in between the boulders for the ponds, as well as creating a neutral consistent surface inside and out.”

So while the sinuous concrete surfaces dominate the building’s exterior, they briefly stand aside for Portuguese limestone slabs that run throughout the interior, including along some of the walls and floors. Companioned by blonde-coloured timber furniture, also designed by Studio Nicholas Burns, the tactile limestone contributes a softer mood among the chapel’s hard-edged spaces.

Standing in stark contrast to the chapel, the meditation room is the smaller of the buildings in this partnership. Located off to one side, the humble structure strays from the concrete facade of its larger sibling, calling upon stacked shale to hug its exterior walls. The locally sourced rock forms the base of a deeper material palette and places the meditation room in symphony with the natural surrounds. “The stone and the roughness of the application was intended to allow the building to read more like a landscape and to provide niches for the moss and lichen to inhabit over time, strengthening that notion,” Nicholas says.

Inside the meditation room, the depth of materiality continues. The space is lined floor-to-ceiling with dark-coloured timber, partnered with equally warm timber furnishings. The only relief from the piercing blackness is created by a shard of sunlight that pours into the space through a vertical corner window, which also frames a view toward a boulder “floating” over a pool of water. But once the room’s openings are all sealed off, occupants are left to meditate in the darkness – perhaps by candlelight, perhaps in physical solitude – accompanied only by their thoughts and an unparalleled soundtrack performed by nature.

The stone and the roughness of the application was intended to allow the building to read more like a landscape.

Catch up on more architecture highlights and public spaces, plus subscribe to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.