On a late winter’s day with full sun and a brisk breeze, the sliding side panels of a vast Ampelite shed were open. A large almond tree – the first fruit tree to blossom – was vivid white and buzzing with bees. Shadows of birds moved across the roof with a clatter of claws. A pair of masked lapwings voiced their distinctive call. They typically inhabit large grassy areas near open water but have taken to nesting on flat roofs. The Longhouse roof isn’t flat, but perhaps it seemed like an expanse of reflective water from above. Within, all is glowing, leafy-green and very comfortable.

The Longhouse is a 110-metre-long big shed sheltering a sequence of smaller buildings and gardens. Trace Streeter and Ronnen Goren, the couple who built the Longhouse, have lived in it for a couple of years. For three years prior to that, while they were building the house and its garden, they lived in nearby Daylesford, Victoria. What they have built serves as a cooking school, productive garden and living space for themselves, friends and WWOOFers (Willing Workers On Organic Farms).

Ronnen is a graphic designer who still works in Melbourne as a founding partner of 25 years with Studio Ongarato. Trace has relocated from Queensland. “Part of Trace moving from Queensland to Melbourne depended on finding a farm; finding the right site,” explains Ronnen. “Coming from Brisbane he wanted a different experience of climate and landscape.” As Ronnen points out, the week before my arrival it had snowed but outside the Longhouse is a sunny green landscape.

Architect Timothy Hill of Partners Hill was involved from the outset. “We were interested in siting the building, especially as we were very interested in the sequencing, the experience of approaching the building,” explains Timothy. The relationships of the nested buildings to the surrounding land and wider landscape beyond is key to the project. Lying just off the crest of a hill with expansive views, the Longhouse is approached from the rise behind. A switchback road spreads and shifts the surrounding landscape before you as you approach, until finally swinging perpendicular to a long shed, nestled behind grassed mounds and tanks. From outside Mount Franklin is framed in the far distance by the open sliding doors on either side of the shed.

“Ultimately, the idea for the shed structure and the internal spaces comes out of the program and the site,” says Ronnen. “The views are wonderful but being so exposed means we needed protection.” And it was not just humans that needed protecting. Ronnen and Trace wanted to grow fruit, vegetables and herbs, as well as ornamental favourites. These plantings would also need shelter.

Inside the Longhouse are rows of veggies fronted with herbs, scrambling passionfruit vines and secured grapes, fruit and citrus trees, including a massive avocado and figs espaliered against translucent walls. It made sense to protect separate, smaller buildings within a huge shed. The shed could then also shield planting, affording light and views while being able to open up to breezes when the weather was mild. But the architect also saw the project as a chance to rethink the way we relate to landscape. “Doing my first site visit in summer London clothes, straight off a plane, was very revealing,” says Timothy. “It was blisteringly cold.”

The site presented challenges to cultivation, too, including from the attentions of kangaroos, cockatoos and other animals. These non-human residents were part of what drew Timothy’s clients to the site but they would also destroy any new planting that survived exposure to wind and weather. “We saw that neighbours were doing very defensive things to cope with the conditions,” recalls Timothy. “If we look at patterns of colonial and post-colonial farming compared with people who have always farmed in harsh environments – Tunisia and the top of Britain for example – you see the Australian tendency to scatter buildings in the landscape.”

Screen planting then makes buildings and their gardens very inward-focused retreats from a harsh environment. “In the Australian lexicon there’s a lot of romancing of sheds and cottages,” says Timothy. Cottages are good for gazing out of at a landscape that is a place of beauty and fear. They separate you from it. “At the Longhouse you can spend a lot of time ‘inside’ and yet be close to the landscape. You end up spending much more time aware of the landscape. In mid-winter, on a stormy night, you can be in your socks going to the ‘outside’ bathroom!”

Protection then is layered. Within the vast shed, a sequence of smaller buildings of brick and solid cedar includes the residential lodge at the far eastern end, the bathhouse, the kitchen and the stableman or interior gatehouse. The bathhouse and kitchen feature white-glazed brick against earthy terracotta-pink mortar, so that even while being the most solid and protective material of the Longhouse, the effect is cheerfully reflective. In one sweeping view, the white of blossom and bricks, wispy clouds and flocking cockatoos can be taken in.

Looking along the inside airy volume, through the open walls to the valley beyond, Ronnen notes the early trips he and Trace made around the area. “Travelling around the countryside looking at potential sites, the forms that stand out in the landscape are old homestead chimneys.” The brick chimneys lingered in their minds when considering the design of their own hearth and home.

Three different bricklayers were involved in the project. Partners Hill had worked previously with bricklayers Elvis & Rose in Brisbane and brought them down to carry out the complex geometry of the bathhouse. Two brothers from John Tanzen & Sons Bricklayers, who had learnt their trade from their German father and grandfather, built the major wall of kitchen brickwork and hearth. The wall houses various ovens, wood cooktops and a grill and has wonderful niches and overhang.

Ronnen recalls the bricklayers living on site for five weeks while they completed the intricate work. At the end of the space is a bread-baking oven designed by Alan Scott and built by his son Nick Scott. The thermal mass and shape create the perfect oven that will hold a falling temperature for over a week. Ronnen gestures to the bright landscape falling away beyond us to Mount Franklin, and then the glowing confines of the long interior. “In summer when the grass has browned outside, there is a strong contrast with the greenery visible inside the Longhouse,” he admits, “but there is a lot of connection. It’s layered.”

Despite drawing on long traditions of greenhouse planting and terrarium-like closed systems, the Longhouse is not intended to be a biodome. Connections to the outside are vital for healthy planting, including air movement and insect pollination. Closed systems can also enable disease and pests to flourish. A moth infestation destroyed a honeysuckle that originally bloomed over the tea-house timber porch of the lodge. There is ongoing trial and error with species and maintenance. Some espaliered fruit trees proved just too congested, even with heavy pruning.

For Timothy this is about active, civilised engagement with the countryside. To be immersed in landscape and so visibly connected yet protected “creates really deep comfort”. The Longhouse isn’t a weekender. It is not about temporary experience of a deliberately ‘rude’ inhabitation. Just because you are living in the country doesn’t mean you need to be uncomfortable or stagnate. “The imagination is engaged when you invite it to make comparisons,” says Timothy. “Rough with smooth, tiny with massive” and, of course, interior and exterior, light and shade, the long thin skin of the pre-fabricated shed and the solidly crafted interior rooms of raw timber and bright brick.

The goal of the Longhouse project is to be as self-supporting as possible. “We’re not evangelical about it,” Ronnen adds, although they are working toward a system that hopes to grow and recycle everything on site. “We have a deep litter system where the manure of animals at one end of the site is collected and aged as compost, feeding back into the planting, so that essentially everything cycles through as part of a giant composting system.” The whole building project is based on passive house principles.

The concept of the Longhouse draws on archetypes, from Viking to Asian to various indigenous architectures. But central to the type is an idea of community and extended, non-nuclear family, particularly around cooking, meals and the socialisation and conversation that happens with that.

Ronnen remembers the Borneo episode of Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown where the chef returns to a longhouse he had visited 10 years earlier in Sarawak during a formative time in his life. “Community living may not always be the best thing though,” laughs Ronnen, recalling that Bourdain’s communal experience included the peer pressure of drinking until passing out.

The Longhouse is where Ronnen and Trace expect to be for the long haul. They are still experimenting and expect to find more opportunities to grow and prepare food, entertain friends, host events and actively expand on projects. “Perhaps we could have thought through all the stairs,” muses Ronnen as he imagines growing old in the Longhouse. But the beauty of the design is that it can easily grow and adapt. “We can ramp up the number of WWOOFers and helpers who stay here, or even fit out the west end with a more age-friendly living space later on,” he shrugs. Considering the overall openness of the Longhouse, it is surprising that the shed only has one door. But the home within and the ideas running through the expanded building and farming project are still evolving, opening new opportunities for both client and architect. The Longhouse is the start of a new long story.

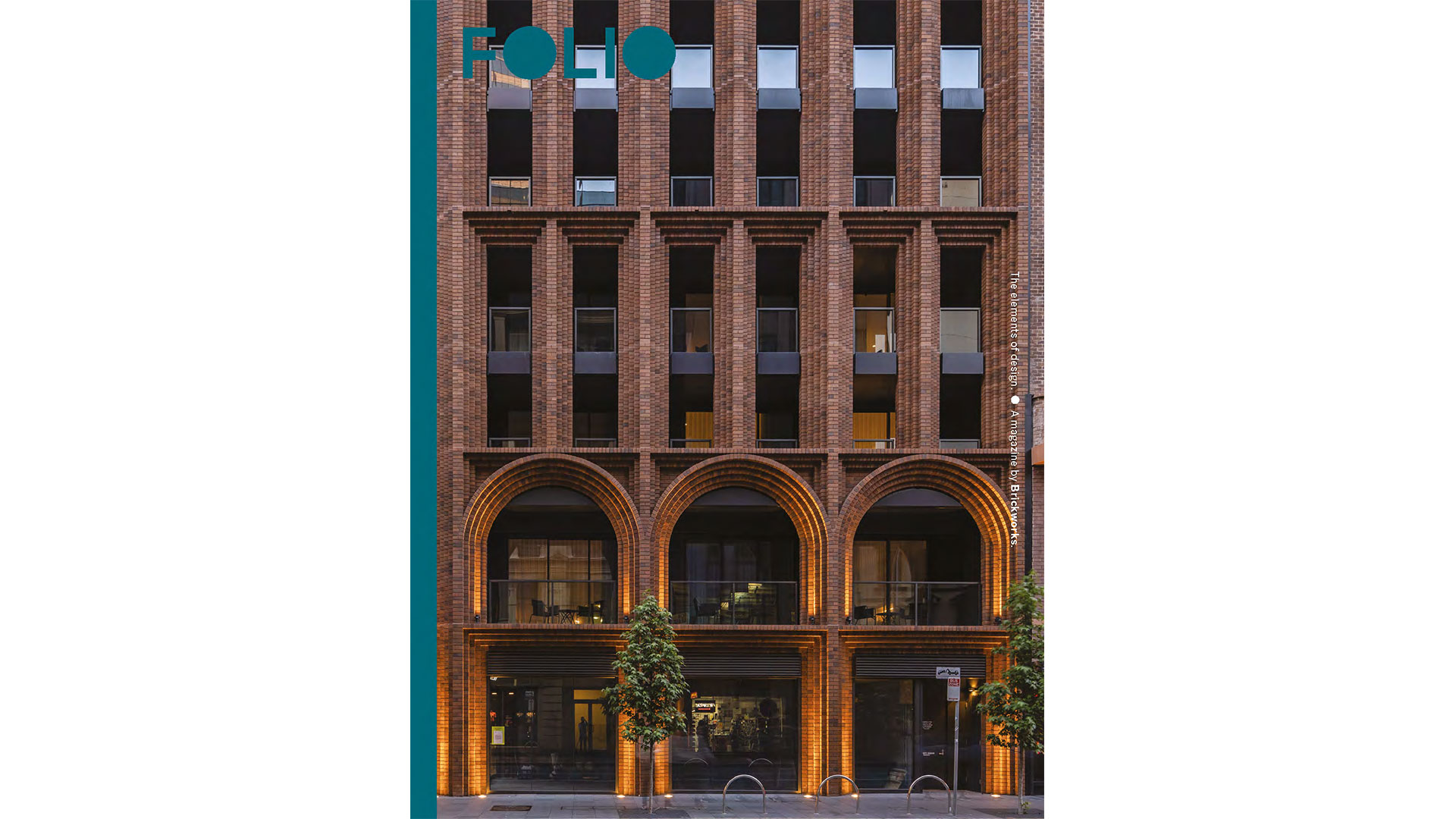

This article has been adapted from a feature that appears in the fourth edition of FOLIO magazine, a publication by Brickworks. Register now for your free copy.