The Beehive is a father-and-son project by architects Luigi and Raffaello Rosselli. Each runs their own practice from this small commercial building, whose name is playfully derived from its cellular brise-soleil, composed of salvaged terracotta roof tiles. In what has become the building signature, the roof tiles are stacked vertically against the four-storey facade, performing the vital task of filtering the hot western sun and helping cool the interiors.

Raffaello was project architect, and Luigi his “informed client”. Having acquired an empty infill site in a heritage row, they started looking for a material waste stream with no existing re-use market. Raffaello’s emerging practice is dedicated to material re-use in construction, furniture and linings.

“I wanted to take things further, and integrate a recycled material into the structure, so when we found out that terracotta roof tiles have no re-use market, we got really excited,” says Raffaello. “Out-of-manufacture roof tiles are collected in Sydney, but newer tiles have no market value – they’re actually considered a cost – and inevitably end up in landfill. That could change with rising tip costs,” says Raffaello.

They didn’t have far to search. A client of Luigi’s wanted to replace the terracotta roof of their large house with slate, so they arranged for the builder to remove the roof tiles carefully and take them to Surry Hills. On site, they played with the roof tiles to resolve the pattern, structural steel tiebacks and aesthetics for the facade’s curve, where it gently bends around a paperbark tree.

How do they perform? “Brilliantly. They block a lot of the hot sun, and because the screen is a tile deep, it doesn’t get hot, or radiate heat internally. The view out is more interesting, and there’s another effect we hadn’t counted on. Terracotta absorbs moisture from nighttime condensation and releases it during the day, so it has a beautiful cooling effect in summer,” Raffaello explains.

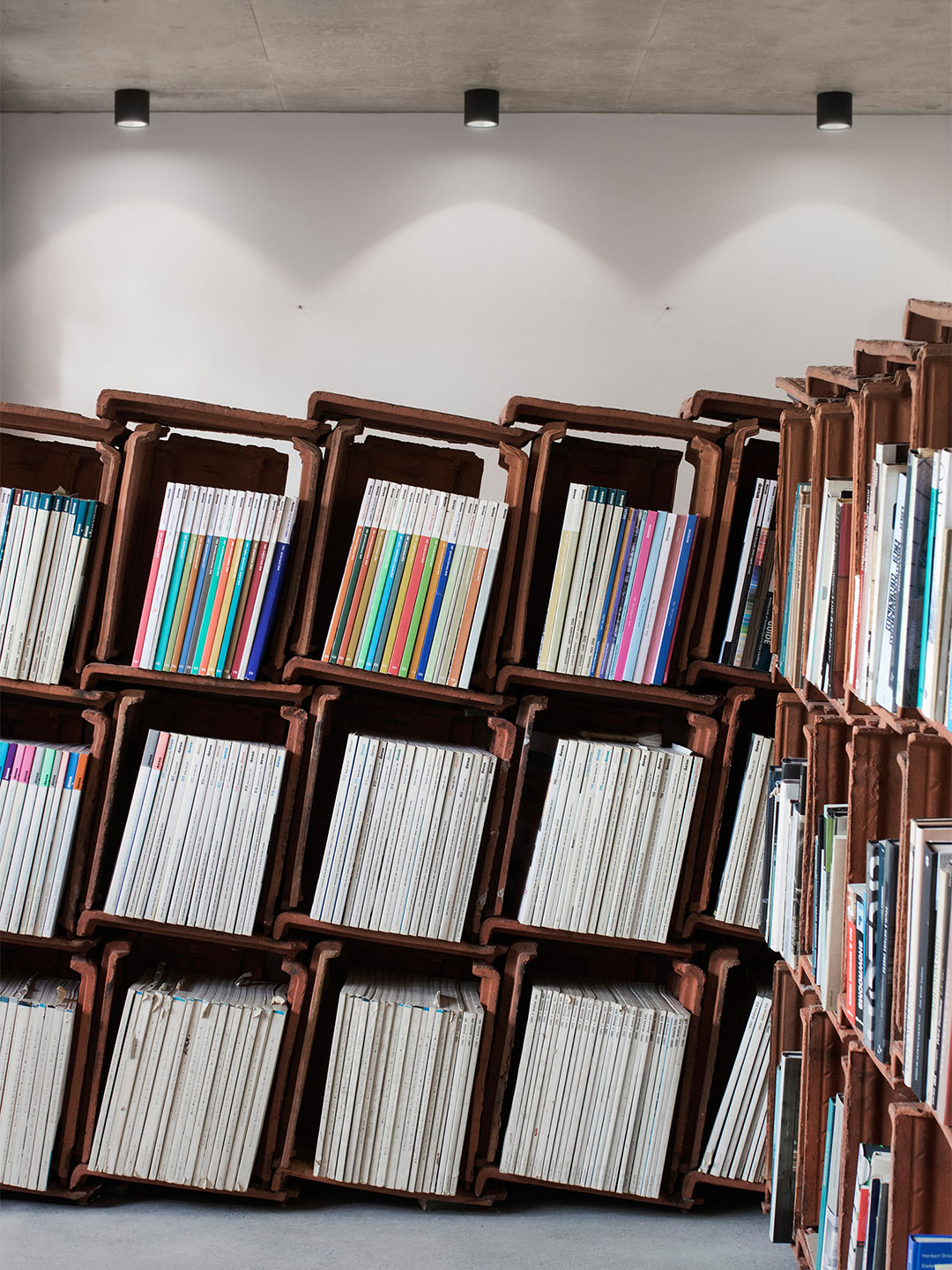

Luigi turned surplus roof tiles from the facade into an L-shaped bookshelf for his studio library, cordoning off a meeting space. It’s furnished with a long table made by Raffaello using black recycled plastic swirled with blue flecks, waxed to a smooth finish. Its A-Joint legs are by industrial designer Henry Wilson, who devised this joint to minimise tooling and parts, while maximising strength.

Chairs around the table are vintage Luigi, designed decades ago for restaurateur Steve Manfredi. “Nothing from the old office was wasted,” says Luigi. “We kept all the desks, repainted some, and had a few identical new ones made.” Other recycled elements include a cute “keyhole” window and its steel mould, with which Luigi plans to make a coffee table. A green rooftop above his studio is also in the planning. “Reusing materials has nearly zero embodied energy. It’s a very important step in reducing the impact of construction, and it’s something we do in all our work,” says Luigi.

People come to us not sure if they should demolish or keep, and almost always we say, ‘keep it’. That’s our ethic.

Luigi Rosselli has built his practice on the artful recycling of old buildings. “People come to us not sure if they should demolish or keep, and almost always we say, ‘keep it’. That’s our ethic. If it’s usable, and not falling down, we say keep and improve what you already have. Many would say that it’s cheaper to demolish a house then rebuild it. But if there was a demolition tax – which there should be – to put a value on materials thrown into landfill, these big houses would be too expensive to demolish.”

His thinking clearly took root in young Raffaello, whose early material upcycling include the Tinshed House in Redfern NSW, and Plastic Palace – an installation to raise awareness about the plastic waste crisis in the NSW border town of Albury, built from five weeks’ worth of local hard plastics (mostly toys, outdoor furniture, car bumpers, crates and boxes), sorted by residents then crushed into bales.

“There wasn’t a lot of precedent when we started the project. But I’ve always been interested in the qualities of old materials, like roof tiles. Their life is expressed through the little nicks and imperfections, and lichen. There’s a poetry to that, that can’t be mass produced,” says Raffaello. “As architects, we can set the value of materials through our work. I think you can make any material beautiful.”

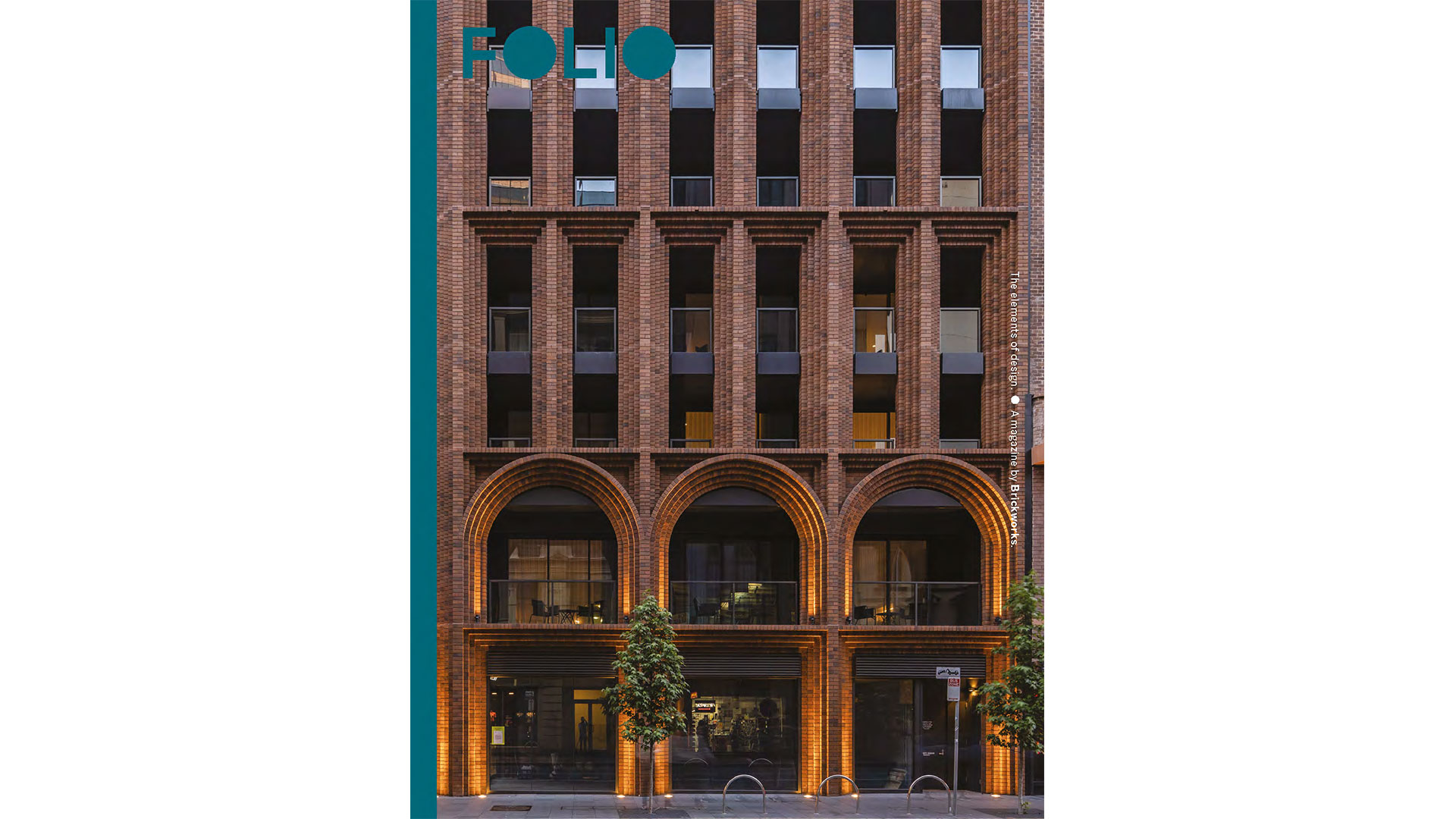

This article was first published in the fourth edition of FOLIO, a magazine by Brickworks. Register now for your free copy.