Found along Afghanistan’s ancient silk road, about 240 kilometres north-west of Kabul, Bamiyan Valley cradles the cultural and political affairs of the Hazára ethnic group. The valley is well-known for its abundance of natural and artistic beauty, as is its capital city, Bamiyan, the heart of the broader Bamiyan Provence. Headlining the region’s attractions is Band-e Amir Lake, with its dazzling azure waters haloed by natural travertine walls, and the ancient remains of the Zahak, Ghulghula and Buddha castles. But a newcomer by way of the Bamiyan Cultural Centre is expected to quickly climb the ranks, cementing itself as a much-loved destination for both tourists and the local community.

The centre arises in the wake of tragic events that date back over twenty years, to March 2001 when the Taliban destroyed two colossal Buddha statues that towered over the Bamiyan Valley. The statues, carved into the stone cliff-face approximately 1500 years ago, were considered the largest standing Buddha sculptures in the world, forming an integral part of both Buddhism and local culture. Tasked with safeguarding the remaining historical artefacts while also promoting new social and cultural developments in the region, the Bamiyan Cultural Centre was born from a 2014 international design competition, spearheaded by UNESCO with the economic support of the South Korean government.

Bamiyan Cultural Centre in Afghanistan by M2R Arquitectos

Selected from over 1000 competition entries, the proposal by Argentina-based design office M2R Arquitectos was announced as the winner, not least for its intentions to create a new and vital centre for communicating and sharing ideas in the Bamiyan region. “Our proposal tries to create not an object-building, but rather a meeting place,” the M2R Arquitectos team explains, pointing to the building’s nearly completed system of internal and external spaces, where the impressive landscape intertwines with the rich cultural activities that the centre will foster. These include permanent and temporary exhibitions, education and training sessions, lectures and cross-cultural performance events.

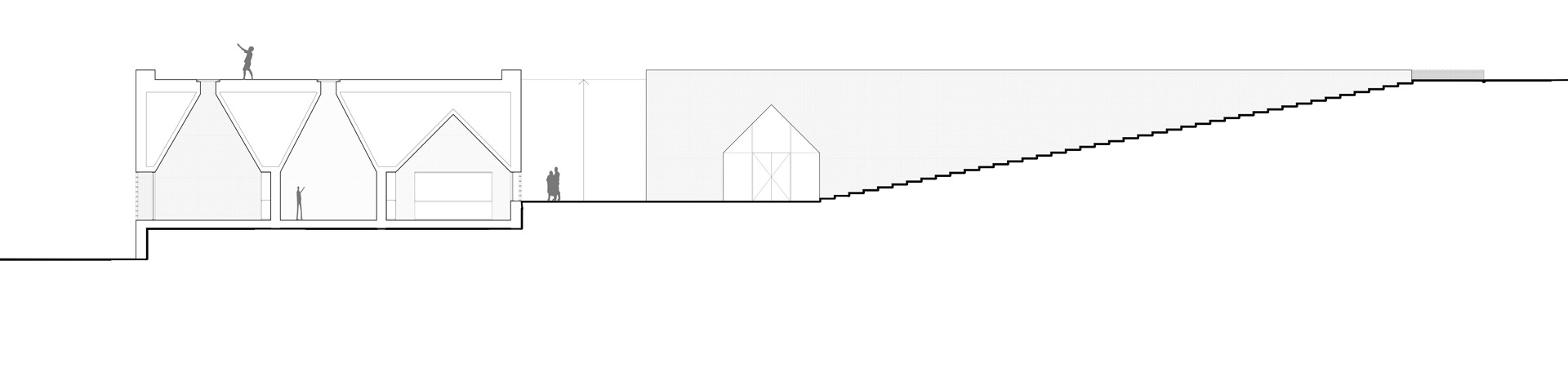

Due to the way in which the underbelly of the building is carved into the earth, the architects suggest the Bamiyan Cultural Centre is not simply built, but rather discovered. “This primordial architectural strategy creates a minimal negative-impact building that fully integrates into the landscape,” the M2R team explains. “It takes advantage of the thermal inertia and insulation of the ground,” they add, highlighting that the interiors of the centre are capable of remaining cool on the hottest of days. This is assisted by the use of slimline masonry bricks throughout the campus which offer a nod to the vernacular architecture of the region, where timber-framed brick and stone homes and public buildings are constructed to tackle the extreme climatic conditions.

When visitors first approach the centre, from the crest of the taupe-coloured escarpment, rather than finding a building hovering over the landscape they will first encounter a public garden, open to all of Bamiyan’s residents. Yet to be realised, the gardens will occupy the uppermost rooftops of the centre, adding to a series of viewing platforms where visitors and locals can meet, contemplate the diverse landscape and peek into the activities happening inside the facility. The centre itself, located beneath the entry level, forms a new man-made cliff face, drinking in unobstructed panoramic views across the Bamyan Valley and what remains of the “Buddha cliffs”.

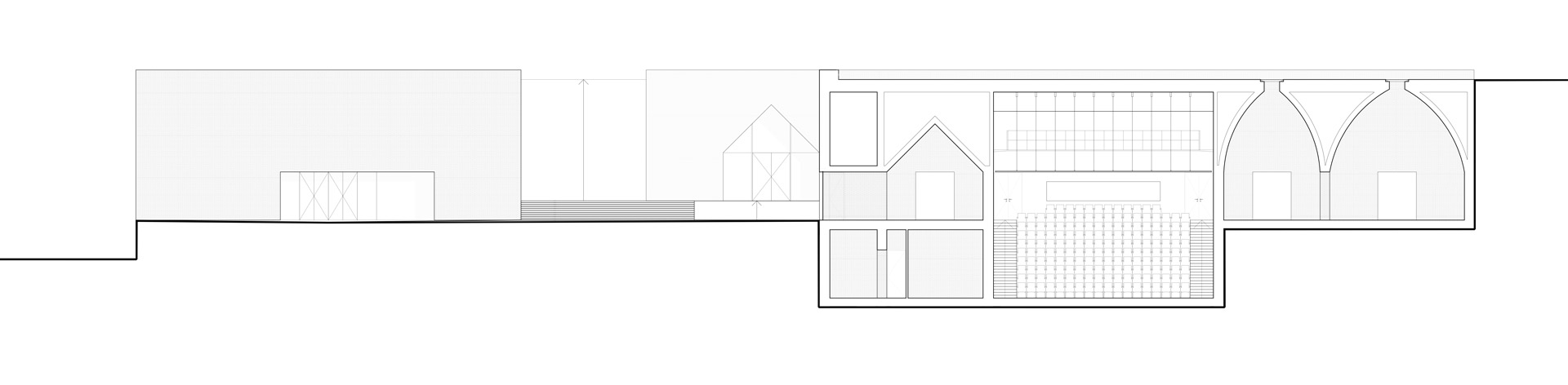

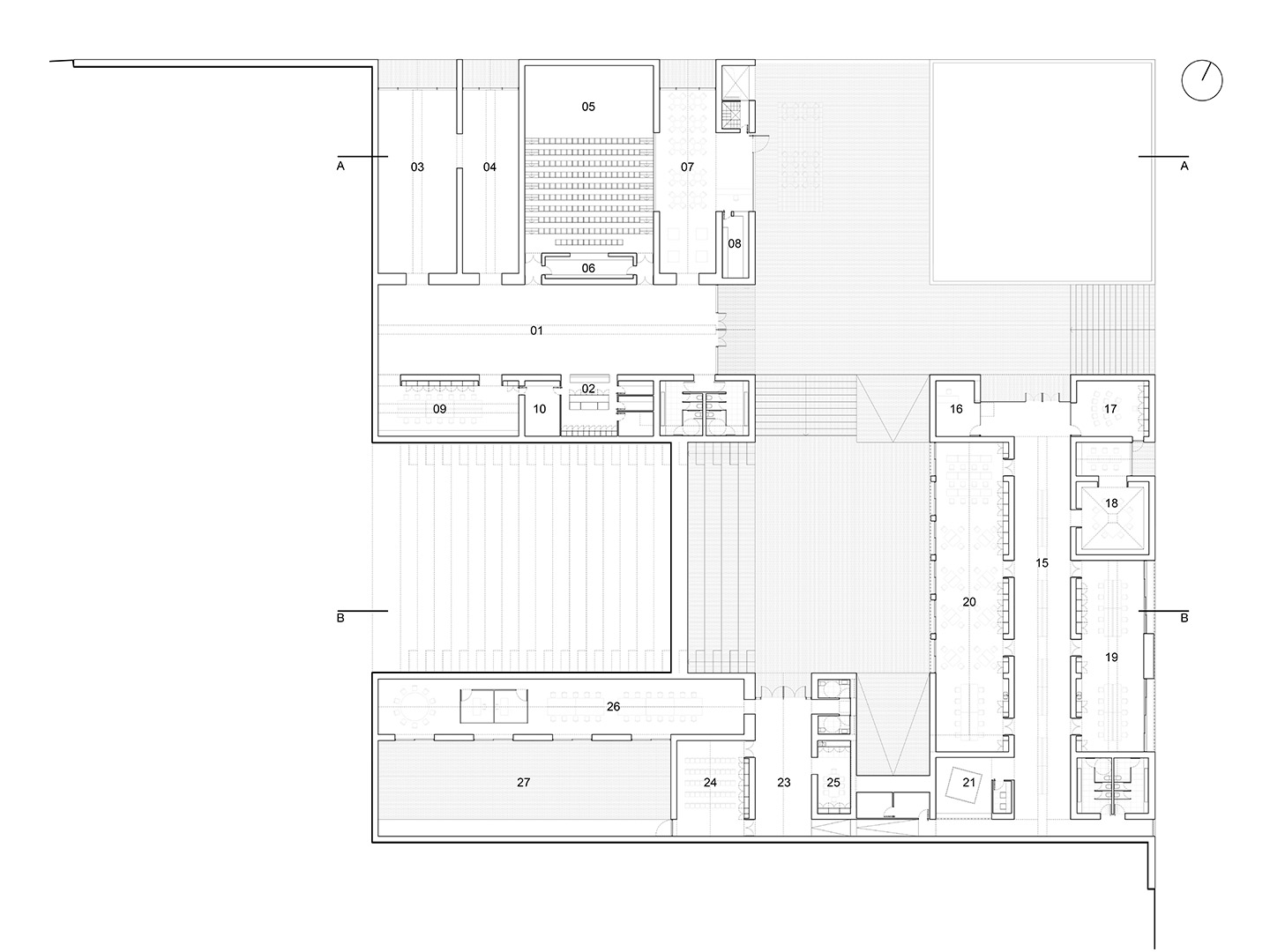

Aligned with the stone niche where the giant western Buddha once stood, a gentle ramp guides visitors down the site to a plaza that serves as the “vital core” for the centre. “This plaza will be an open space for cultural activities,” the M2R team points out, noting that the plaza and surrounding interstitial spaces are formed by the three buildings within which the program is divided. The public activities of the centre are hosted in the Performance and Exhibition Building, the Research and Education Building hosts the semi-public activities of the program and the Administrative Building facilitates the private activities. “This division of the program into seperate buildings allows each to work independently, reducing the cost of maintenance and heating,” the architects explain.

Inside the centre, the cavernous spaces are mostly devoid of discernible detail or ornament. Only the quiet patterning offered by pale, elongated bricks embellishes the floor and walls. Offsetting this, shafts of intense sunlight act as graphic strikethroughs that enter the vaulted rooms via slender cavities overhead. “By their sheer austerity, [the interiors] favour a contemplative and reflective attitude,” the M2R team says. “The skylights of the cultural centre create lines of light that move, following the path of the sun through the sky, making visible the passage of time.” The vaulted elevation of the exhibition area faces the western Buddha niche and frames the views towards it, giving a dramatic historic backdrop to the centre’s contemporary cultural manifestations. “This makes visible the contrast and continuity between Afghanistan’s past and present,” the architects conclude.

By their sheer austerity, [the interiors] favour a contemplative and reflective attitude.

Catch up on more of the latest architectural gestures and commercial design. Plus, join the mailing list to receive the Daily Architecture News e-letter direct to your inbox.